English translation of this study by Michaéla C. Schippers, John P. A. Ioannidis and Matthias W. J. Luijks

(Een beschouwing en korte samenvatting is hier te lezen.)

Like an army of ants trapped in an ant mill, individuals, groups and even entire societies are sometimes caught in a Death Spiral, a vicious cycle of self-reinforcing dysfunctional behavior characterized by continuous wrong decision-making, myopic one-sided focus on one (set of) solution(s), denial, distrust, micromanagement, dogmatic thinking and learned helplessness. We propose the term Death Spiral Effect to describe this downward spiral of social decay that is difficult to break.

Specifically, in current theory-developing research, we aim to:

- Define and describe the Death Spiral Effect more clearly;

- model the downward spiral of social decay and an upward spiral;

- describe how and why individuals, groups, and even society as a whole can become entangled in a Death Spiral; and

- provide a positive path forward in terms of evidence-based solutions to escape the Death Spiral Effect.

Management theory points to the occurrence of this phenomenon and offers turn-around leadership as a solution. At the social level, strengthening democracy can be important.

Previous research indicates that historically, two key factors have triggered this type of social decay: increasing inequality, creating an upper layer of elites and a lower layer of masses; and declining (access to) resources.

Historical main characteristics of social decay are a sharp increase in inequality, overreaching of the government, overintegration (interdependence in networks) and a rapidly declining trust in institutions and the resulting collapse of legitimacy.

Important issues that we want to shed light on are the behavioural underpinnings of decline and the question of whether and how social decline can be reversed.

We explore the extension of these theories from the corporate/organizational level to the society level and use insights from theories at the micro, meso, and macro levels (e.g., Complex Adaptive Systems and collapsology, the study of the risks of the collapse of industrial civilization) to explain this process of societal decline.

Our overview is further based on theories such as Social Safety Theory, Resource Conservation Theory, and management theories that describe the decline and demise of groups, businesses, and societies and offer ways to reverse this trend.

1 Introduction

Ants depend on each other to survive and often hunt prey together. They use pheromones to locate each other, and they follow the one in front of them. This usually works quite well, although sometimes the ants get trapped in what's called an "ant mill" or "death spiral." This can happen when a subgroup of ants separates from the main group and begins to follow each other. They begin to form a constantly spinning circle, and the ants that end up in this death spiral often die of exhaustion. It has even been observed that dead ants are pushed out of the circle, while the ants continue to spin their circles. This "ant mill" or "circle ant paradox" seems to be the evolutionary price that army ants pay for an otherwise successful strategy of collective foraging (cf. Delsuc, 2003).

The pathological, dysfunctional behavior is the other side of the coin of different functional behavior. Rosabeth Moss Kanter, who studied declining organizations for years, concluded that a process can take place in failing companies that resembles a death spiral (Kanter, 2003). After years of success, these companies struggle to manage processes when the tide turns and problems arise. Instead of looking for solutions with an open mind, companies often get caught up in a death spiral and make decisions that seem rational, such as downsizing and centralized decision-making (cf. Charan et al., 2002; Lamberg et al., 2017). Often, these decisions worsen the situation rather than improve it, and self-defeating habits include denial, complacency, and cost-inefficiency (Sheth, 2007).

Sheth (2007) argues that denial of the new reality and internal turf wars, i.e., territorial impulses, are two dangerous self-destructive habits that can drive a company further into decline. Companies are reluctant to admit that they are in trouble and instead blame circumstances beyond their control (Lorange and Nelson, 1985; Charan et al., 2002). Management research has also shown that long before the crisis within a company becomes apparent, the signs are there, but often go unnoticed or ignored (Lorange and Nelson, 1985; Fitzgerald, 2005). Having to address these problems later often leads to drastic steps and overreactions that can further fuel the decline (Lorange and Nelson, 1985; Hafsi and Baba, 2022).

Fitzgerald uses the metaphor of a heart attack in a company and distinguishes between a hidden, subtle and an overt phase of deterioration on the one hand (Fitzgerald, 2005). In the hidden phase, denial or willful blindness often prevents management from taking (the right) actions. Against their better judgment, they hope that if they ignore it, the market will not notice. In that phase, on average, a third of a company's competitive value is lost.

When a new market challenge presents itself, the company is often unable to meet the challenge. In the subtle phase, the deterioration becomes more apparent to those who pay attention and know where and how to look and how to interpret what they see. By the end of this phase, two-thirds of the company's competitive value has often been lost. Unfortunately, many companies only start to admit and address the problem in the open phase. By that time, the problems are so big and deep-rooted that it has become extremely difficult to tackle them. While many managers keep an eye on the company's financial figures, they often neglect to address other metrics, such as trends in market share, customer churn, and employee satisfaction. Often, these factors are the earliest predictors of business performance.

Major barriers to performance include mistrust, bureaucracy, and low performance expectations, while drivers include decisiveness, responsibility, and recognition of work. It is important to identify and quantify early warning signs, e.g., an excess of staff, especially managers, a decrease in lower-level employees, tolerance for incompetence, and a lack of clear goals (Lorange and Nelson, 1985). Reversing organizational decline starts with the realization and recognition that the organization is in decline. These danger signals must then be linked to a concrete plan for change. A dialogue is needed between top-down and bottom-up (Lorange and Nelson, 1985). If the company is able to take these steps, follow-up monitoring is needed to ensure that the proposed and implemented changes are effective (Lorange and Nelson, 1985). While in the early phases too little reaction may be the problem, in later phases the danger of too much reaction comes (cf. Lai and Sudarsanam, 1997; Hafsi and Baba, 2022).

We believe that similar processes can occur at the societal level. Recent examples of societal systemic shocks include 9/11, the global financial crisis of 2008, and the COVID-19 crisis (Centeno et al., 2022). At the societal level, researchers studying policy success and failure have begun to investigate the role of policy under- and over-reactions (Maor, 2012, 2020). Policy overreactions are "policies that entail objective and/or perceived social costs without providing compensatory objective and/or perceived benefits." (Maor, 2012; p. 235). For example, preemptive overreaction is a form of policy that will often rely on persuasion by presenting "facts" in a certain way, creating a perceived threat, and using messaging to influence public sentiment (Maor, 2012). An example is the culling of all pigs in Egypt during the swine flu crisis in 2009, even though zero cases had been reported (Maor, 2012). An important explanation is that in such cases groupthink can play a role. Groupthink, the forced conformity to group values and ethics, has symptoms such as collective rationalization, belief in inherent morality, stereotypical views about outgroups, pressure on dissenters, and self-appointed mind guards (Janis, 1972, 1982a,b; Janis et al., 1978). Preemptive overreaction shows that one acts forcefully and decisively against a perceived threat, which may never materialize, and motives can be political and/or monetary gain (Maor, 2012).

While the period before the COVID-19 crisis may have been characterized by a relative policy underreaction to complex social problems, also known as "wicked problems", such as hunger and poverty (Head, 2018; Head B.W. 2022), the current time can be characterized by an overreaction to certain problems. The COVID-19 crisis seemed to be characterized by groupthink and escalation of commitment to one course, at the expense of other possible solutions (Joffe, 2021; Schippers and Rus, 2021). Low-quality initial decision-making was followed by decisions that made things worse (Joffe, 2021; Schippers and Rus, 2021). The sheer scale and severe disruption caused by these policies has increased inequality (Schippers, 2020; Schippers et al., 2022), an important marker of social decay (Motesharrei et al., 2014).

A metatheory that explains such disruptive events is the Complex Adaptive Systems Theory, a theory that suggests that developments in systems of many parts are often non-linear and that systems, such as societies, exhibit unexpected and self-organizing behavior (Lansing, 2003; Holovatch et al., 2017). Furthermore, "mechanisms such as tipping points, feedback loops, contagions, cascades, synchronous failures, and cycles that may be responsible for the collapse of a system are fundamental characteristics of any complex adaptive system and can therefore serve as a useful common denominator from which collapses can be investigated" (Centeno et al., 2022; p. 71).

In today's society, our survival increasingly depends on closely linked complex and fragile systems (e.g. supply chains), for which no one bears responsibility (Centeno et al., 2022). The potential for modern-day collapse makes it more compelling than ever to learn from past collapses in order to gain insight (Centeno et al., 2022) and to study global patterns of behavior. The normative basis for our document has to do with "the greater good": What is considered good for the flourishing of humanity is seen as "good" or "functional," while what is seen as "bad" or "dysfunctional" are behaviors or decisions that harm the flourishing of humanity.

2 Downward spiral

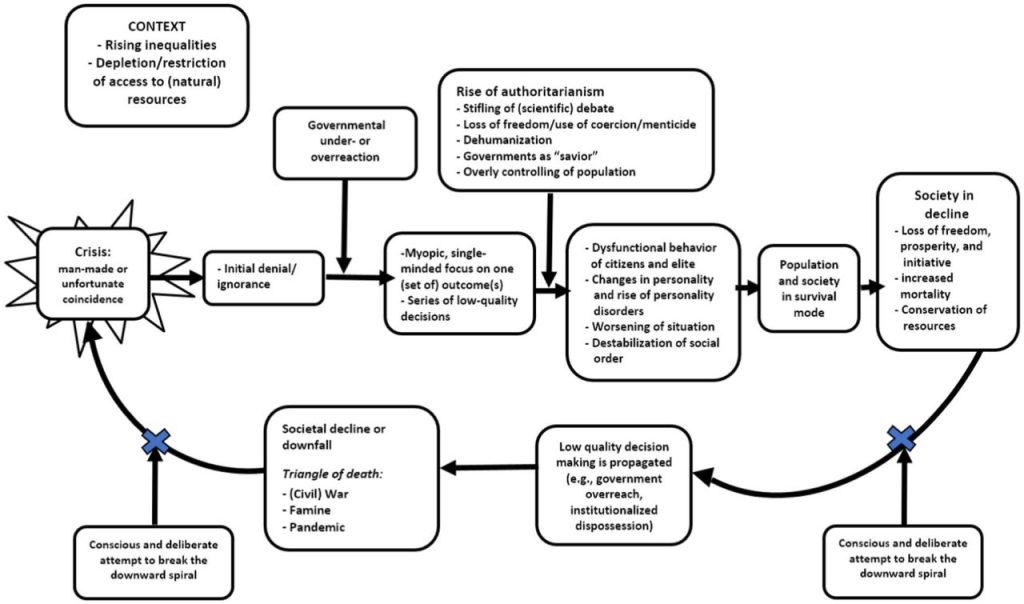

In the current narrative and theorizing, we use the term 'Death Spiral Effect' to describe this type of overreaction and the resulting cascading effects in policies that affect the general public. We review the current literature and extend the theory of complex adaptive systems to construct our theoretical model of collapse and reversal of societal decay. We see the Death Spiral Effect as a specific form of complex (mal)adaptive behavior that accelerates decay and makes it difficult to reverse decay. Using the ant-mill metaphor, we theorize that a Death Spiral Effect occurs when a society becomes entangled in a dysfunctional mode of behavior. By using this metaphor, we want to help with the formation of theories around this construct (Shepherd and Suddaby, 2016). We describe the elements of this vicious downward cycle, such as increasing inequality, dysfunctional behavior of both the elite and the masses, and the rise of authoritarianism. We investigate how the behavioral underpinnings of the resulting environment can lead to escalation through war, famine, and pandemics.

Although there is a rich literature on early warning signs and markers of social decay, the underlying mechanisms have received much less attention and the explanations often lack the depth that psychological, sociological and management theories can provide. We draw on theories such as collapsology (the transdisciplinary study of the risk of collapse of industrial civilization), Complex Adaptive Systems Theory, Social Security Theory (which focuses on developing and maintaining friendly social ties), Conservation of Resources Theory (which focuses on obtaining and conserving resources), and general management theories describing the decay of groups. We also use Social Dominance Theory to explain how and why the resulting inequalities are difficult to reverse (Pratto, 1999; Pratto et al., 2006). Our work is also related to X-risk studies, a field of study that looks at existential risks to humanity (Torres, 2018; Moynihan, 2020): We recognize the importance of cascading risks, and hint at how catastrophic (X) risks could potentially be combined to compromise human survival (Torres, 2018; Baum et al., 2019; Moynihan, 2020; Undheim and Zimmer, 2023). We use a 'Big Picture' approach to these issues (Campbell et al., 2023). We then outline a possible upward spiral, dissecting which elements are needed to reverse the death spiral and build a society in which people can thrive and be prosperous. In this way, we contribute to the formation of theories about the psychological and sociological drivers of social decline (Swedberg, 2016). Our goal is to contribute to knowledge about societal decline and prosperity in order to increase humanity's chances of flourishing.

2.1 Crisis and crisis management

Several authors have noted that societal downturn has similar phases to organizational downturn in firms, including early warning signs (Tainter, 1989; Downey et al., 2016; Scheffer, 2016; Jones, 2021; Demarest and Victor, 2022). Compared to decline in organizations, however, the scale on which this happens is larger, the social consequences are more complex and the decline is often a more lengthy process. The average lifespan of a company in the Standard and Poor's 500 index in 2020 was 21.4 years (Clark et al., 2021), while some historical empires have lasted many decades or centuries (Taagepera, 1979). Another difference between organizations and society is that the outcome of the downturn often cannot be buffered by society, as would be the case with the downturn of companies. The harsh outcomes (including war, famine and widespread disease) can also be very difficult to reverse (Downey et al., 2016). These three, war, famine and pandemics, we call the "Triangle of Death", a phrase coined by former Green Beret and combat correspondent Michael Yon (Yon and Peterson, 2022). However, Demarest and Victor (2022), p. 788 note that: "Even today, the greatest challenge to knowledge arising from collapse studies – relevant not only to policymakers and managers, but to the citizens of the whole society – is that no one really deeply believes that total collapse is possible".

The process of societal decline is complex and can include socio-ecological pitfalls, or a mismatch between people's responses and the social and environmental conditions they face, e.g., depletion of natural resources (Boonstra and De Boer, 2013; Boonstra et al., 2016).

For the current evaluation, we consider that the approach to the COVID-19 crisis may have been an example of overreaction by using non-pharmaceutical interventions that accelerated existing societal problems, such as inequality (Schippers, 2020; Schippers et al., 2022). Most countries opted for very similar solutions, with forced closures and aggressive restrictions. Countries that chose a different course received a lot of criticism (Tegnell, 2021). Many countries ended up experiencing mortality rates that were very unevenly distributed across groups, exacerbating existing inequalities (Alsan et al., 2021; Schippers et al., 2022).

Overreactions were fuelled by (unreliable) measurement data (Schippers and Rus, 2021; Ioannidis et al., 2022) and groupthink, resulting in irrational or dysfunctional decision-making (Joffe, 2021; Hafsi and Baba, 2022). In addition, emotions often run high during crises, increasing the risk of damaging overreactions from both policymakers and the general public (Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2010). Governments can suffer from an action bias, a tendency to take action whether it is necessary or not, including excessive actions (Patt and Zeckhauser, 2000) despite information that policy can do more harm than good (for reviews see Joffe and Redman, 2021, Schippers and Rus, 2021; Schippers et al., 2022). Unnecessary crisis response as a form of overreaction to policy can sometimes occur as a way to shape voters' perception of a decisive and active government (Maor, 2020). Over-acting and exerting control over societal structures, for example in the field of public health, can reinforce the centralization of power and decision-making and authoritarianism (Berberoglu, 2020; Desmet, 2022; Schippers et al., 2022; Simandan et al., 2023). When governments use mass media to disseminate negative information, a self-reinforcing cycle of nocebo effects, "mass hysteria" and policy errors can arise (Bagus et al., 2021). This effect is amplified when the information comes from authoritative sources, the media is politicized, social networks make the information ubiquitous (Bagus et al., 2021) and dissenting voices are silenced (Schippers et al., 2022; Shir-Raz et al., 2022). This can lead to a vicious cycle of ineffective crisis management, low-quality decision-making, and dysfunctional behavior, which intensifies the current crises and leads to new ones, and ultimately societal decline and even collapse.

According to Holden (2005), p. 651, a complex adaptive system is "a collection of individual agents with freedom to act in ways that are not always fully predictable and whose actions are interconnected. Examples are a termite colony, the financial market and a surgical team". An important element is emergence, the idea that complex global patterns can arise from local interactions (Lansing, 2003). In the current article, following authors such as Buckley (1998) and Lansing (2003), we see society as a complex adaptive system, with nested systems such as organizations and governments as part of the larger system. We suggest that the adaptive system is entering an unstable time, in the form of a series of crises. We extend the Theory of Complex Systems by adding the Death Spiral as an element, where the system becomes so unstable that actors within the network start to hold on to repetitive maladaptive (decision-making) behavior (Schwarzer, 2022); making the same decision over and over again, leading to undesirable outcomes such as war, famine and pandemics (Triangle of Death) and ultimately the demise of society. In doing so, we explain the underlying mechanisms of social decay and outline possibilities for reversal.

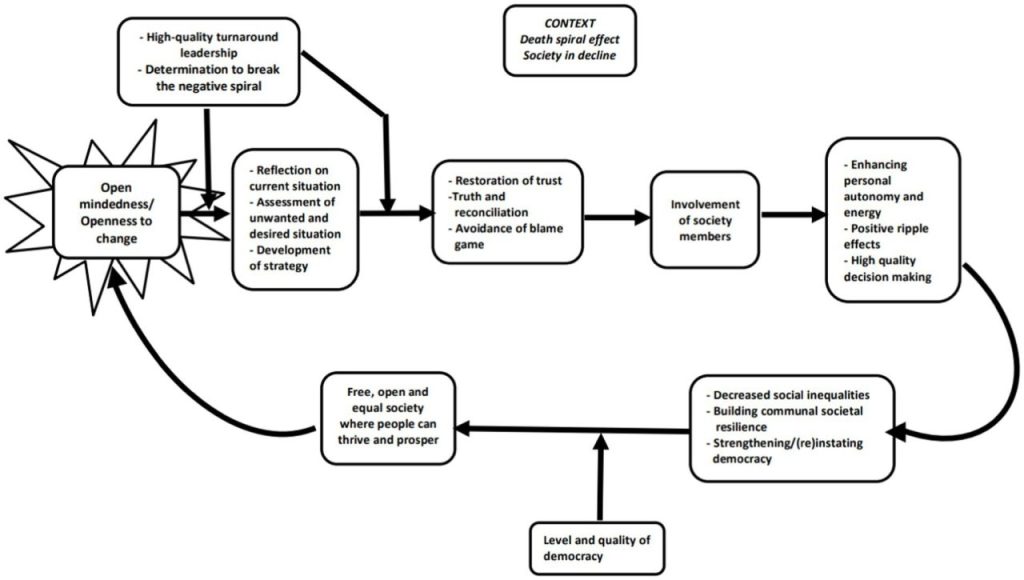

Below, we will first define and describe the process of a Death Spiral, and the similarities and differences between a Death Spiral and other concepts such as groupthink and mass formation. We will do this in the context of the more meta-theory of complex adaptive systems. Second, we will describe the elements of a societal downward (death) spiral, such as low-quality decision-making, rise of authoritarianism, and dysfunctional behavior of both the elite and the masses (see Figures 1 and 2). We will do this in the context of both historical and current examples. Thirdly, we describe the possibilities for a virtuous circle, for example the presence of high-quality turn-around leadership, restoration of trust and the development of a turn-around strategy.

2.2 Considerations on the death spiral

When people and groups experience difficulties or trauma (or sometimes for no apparent reason), they may start making decisions that do not ensure survival, but seem self-destructive at best (cf. Balcombe and De Leo, 2022). They can make decisions to deal with the situations, but these can be characterized as maladaptive, non-adaptive or semi-adaptive (Marien, 2009). Attempts to escape a downward spiral sometimes make it worse, by using counterproductive coping mechanisms (e.g., Freyhofer et al., 2021). Dysfunctional behaviour continues if the spiral is not broken, and decay can result from increasingly fragmented political institutions (cf. Kreml, 1994). In terms of the Complex Adaptive Systems Theory, the system then enters an unstable time, in this case a crisis (Centeno et al., 2022). When the system takes a hit, for example due to financial decline, resource depletion or other fortune twists (Motesharrei et al., 2014), groups or societies may feel compelled to take action without properly considering whether their decision-making process is valid (cf. Schippers et al., 2014). The threat-rigidity effect predicts a limitation in information processing and a narrowing of control under conditions of threat (Staw et al., 1981). The whole system becomes unstable and dysfunctional behavior occurs (Mohrman and Mohrman, 1983). The environment generally becomes stressful and threatening, which increasingly provokes self-protective and rigid behavior, which further threatens the stability and survival of the group (Staw et al., 1981).

Finally, individuals and groups may tend to go through their lives in "circles" and repeat the same mistakes, seemingly trapped in one behavioral mode. In organizations, similar Death Spiral pathologies can arise when changes in the environment do not provoke adaptation, but secrecy, guilt, avoidance as well as passivity and learned helplessness (Kanter, 2003). In the general management literature, dysfunctional behaviour is often described as a form of antisocial behaviour, intended to cause harm (e.g. Giacalone and Greenberg, 1997; Van Fleet and Griffin, 2006). In the current article, dysfunctional behaviour is seen as counterproductive or ineffective behaviour, which may have outlived its usefulness and does not have the intended effect and can even have (unintended) harmful consequences (Robinson, 2008). In companies, dysfunctional or counterproductive work behavior undermines efficiency and can go from social loafing (making less effort when working in a group than when working alone), conflict and retreat to theft, fraud, bullying and even murder (Robinson, 2008). The more "civilized" forms of dysfunctional behavior, such as social loafing and withdrawal, are the most common (Robinson, 2008) and these can be much more common in organizations and societies that are in a downward spiral and undermine individual autonomy. People who feel powerless in organizations that exercise too much power are often triggered to engage in counterproductive work behaviors (Lawrence and Robinson, 2007). During the COVID-19 crisis, withdrawal effects became more widespread and the crisis led to changes in attitudes towards work and to changing work behaviour within organisations (Newman et al., 2022). For many workers, stress levels increased and work performance declined (e.g., Vaziri et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2021).

At the organizational level, decline often leads to aversion and distrust between managers, who then avoid each other, hide information and reject blame (Kanter, 2003). People within the organization no longer act in consultation and the decreasing chance of success of their actions makes them feel helpless (Kanter, 2003). In such situations, managers often resort to micromanagement: they try to control employees' actions down to the smallest detail to make them productive again. The reaction of employees will be to misbehave as a form of organizational resistance (Lawrence and Robinson, 2007), causing cycles of micromanagement and counterproductive work behavior to reinforce themselves (see Jensen and Raver, 2012; Cannon, 2022). A toxic work or societal culture can emerge that persists for some time, with fear as the predominant principle (Cannon, 2022). In society as a whole, the dangers of a "toxic discourse" around impending disasters (Buell, 1998; Horfrichter, 2000) may pave the way for drastic measures to prevent such disasters (Schippers, 2020). However, some measures taken to prevent these hypothetical or expected future disasters have caused damage, leading to a sharp increase in poverty and inequality (Schippers et al., 2022). In addition to many layoffs, many people have thought about their working lives and then decided to quit their jobs. The resulting "Great Resignation" seemed to be a global phenomenon (Jiskrova, 2022; Sull et al., 2022; Del Rio Chanona et al., 2023). In the United States, monthly layoff rates were higher than in the previous 20 years (Statistics, 2021; Jiskrova, 2022). Notice that many employees changed jobs and did not completely withdraw from the labor process ("Great Reshuffle"; Sull et al., 2022). However, at the beginning of 2021, more than 40% of employees were thinking about quitting, citing a toxic work culture as a major reason (Sull et al., 2022). At the same time, the decline in organizations was often caused by the COVID-19 crisis and non-pharmaceutical interventions carried out to combat the spread of the virus, such as the closure of restaurants and "non-essential" stores (Brodeur et al., 2021). As early as April 2020, the number of active business owners in the United States dropped by 22% within just 3 months (Fairlie, 2020; Brodeur et al., 2021). Together with other consequences, such as increasing inequality, increase in immigration, altered labour market, damaged mental health and well-being, this is arguably a major shock to societal cohesion (Silveira et al., 2022), increasing the fragility of the state and reducing the legitimacy of the state (Seyoum, 2020).

Both in society in general and in many companies, toxic cultures can emerge during crises (cf. Meidav, 2021). In such cultures, behaviour that management or the government wants to see is rewarded, while many (mis)practices remain unchecked, creating room for fraud and corruption (cf. Kerr, 1975; Meidav, 2021; Breevaart et al., 2022). Indicative of such a toxic culture are: (reduced) degree of helpfulness of people, (in)formality and (blind) enforcement of rules, the underground avoidance of rules, the feeling that things can be better but also the feeling of not being able to change them, complaining "around the water cooler," loss of morale, lack of initiative, top-down decision-making, "double speak, " and lack of cohesion (Cannon, 2022). People are generally willing to do the right thing but find many roadblocks when they try (Myers, 2008). Moreover, historical research has shown that people fall back on "learned" comfort behaviors, which causes prejudices to become ingrained again. For example, the decline in preference for ingroups causes diversity efforts in companies to decrease during crises and inequality to increase (Meidav, 2021). During organizational change, employee misconduct increases (Ethics and Compliance Initiative, 2020; Meidav, 2021), including even antisocial behaviour (Belschak et al., 2018).

2.3 Death spiral effect: definition and main characteristics

Based on the above considerations, we formally define the Death Spiral Effect as: A vicious circle of self-reinforcing dysfunctional behavior, characterized by continuous flawed decision-making, myopic one-sided focus on one (set of) solution(s), resource loss, denial, distrust, micromanagement, dogmatic thinking and learned helplessness. The death spiral is often triggered by an external or internal event (e.g., crisis) that triggers a trauma or emotional reaction. In the case of man-made crises, a positive feedback loop of perverse incentives can cause a stable society to spiral into disorder (Centeno et al., 2022). The death spiral effect occurs when a cascade of events is difficult to stop once set in motion (cf. Centeno et al., 2022). On a societal level, this spiral results in a widening gap between elite and masses, increasing authoritarianism, and massive loss of resources. For example, it has been noted that ancient civilizations on the brink of collapse used scarce resources for megalomaniac projects, such as massive temples, in a desperate attempt to legitimize declining institutions, but ultimately remained on the course of disintegration (Demarest and Victor, 2022).

A death spiral is characterized by: (1) initial denial of the problem; (2) persistent and repeated poor decision-making, often trying to solve the problem with the same ineffective solution over and over again; (3) increasing secrecy and denial, reproaches and contempt, avoidance and protection of territory, passivity and helplessness; (4) deterioration of the situation, and an ongoing (series of) crises that follow, further activating a "survival mode" and tunnel vision, and (5) the felt or perceived inability to escape or break out of the ineffective cycle of decision-making. Other characteristics that emerge when the death spiral becomes apparent are: (1) a negative and distrustful atmosphere; (2) micromanagement: individuals, management or government who try to increase the number of (strict) rules and a focus on complying with those rules at the expense of effective problem-solving; and (3) censorship of opinions and knowledge outside the official narrative. These elements can be present at the same time to varying degrees and reinforce each other. As the downward cycle continues and the loss of resources escalates, the desperation principle can kick in: a defensive mode in which people or groups aggressively and often irrationally try to hold on to the few resources left (Hobfoll et al., 2018), rather than thinking about how to free themselves from the situation.

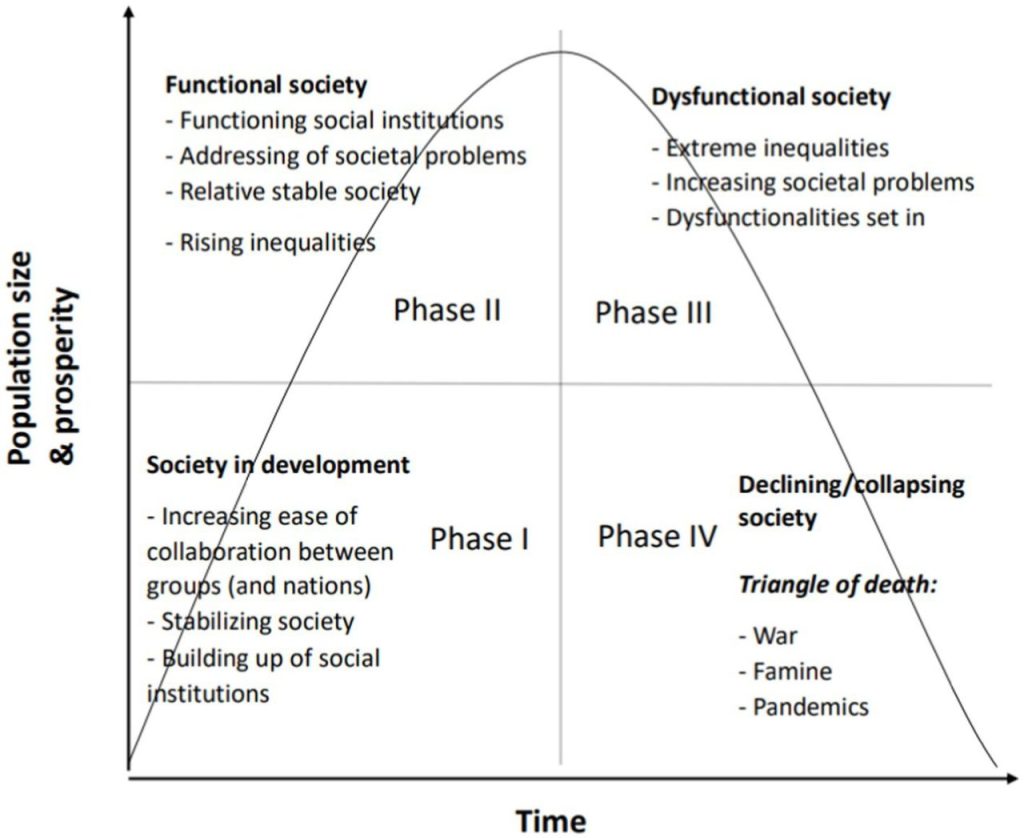

In Figure 2, we distinguish four phases of social development and decline: In phase I, society develops and grows. In this phase, groups work together without major problems. Social intuitions are established and strengthened. In phase II, a functional society is relatively stable, although social inequality is already increasing in this phase. In Phase III, a dysfunctional society, the seeds of discontent sown during Phase II have now matured: social inequalities are becoming more extreme, resulting in an increasing number of societal problems and an increase in societal dysfunctions. Governments often respond via centralization of power and an increase in authoritarianism rather than involving the general public in solving societal problems. In phase IV, we see a declining or collapsing society. If the problems of decay, which began in Phase II and III, are not addressed, society will deteriorate and eventually collapse. Collapse is characterized by the Triangle of Death: War, Famine and Pandemics (Karabushenko et al., 2021; cf. Kuecker, 2007; Yon and Peterson, 2022; see also Figure 1).

2.4 Differences from other concepts

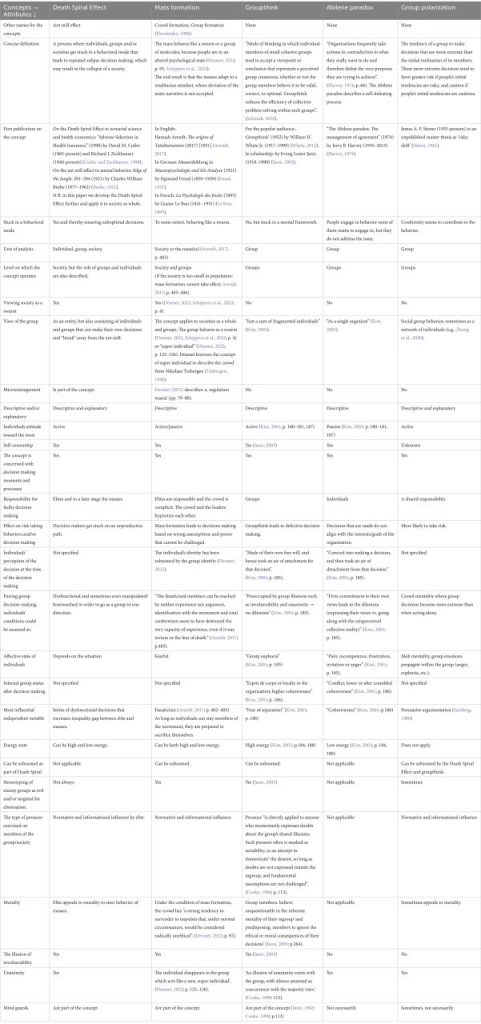

While we define the Death Spiral effect as a specific form of collapse within an adaptive complex system, the concept of a Death Spiral is an overarching concept that has some overlap with, but also distinguishes it from, a number of other concepts, such as groupthink, mass formation, Abilene paradox, and group polarization.

In Table 1, we list these concepts and provide an overview of similarities and differences with the Death Spiral Effect. All these concepts are about forms of dysfunctional decision-making. The main difference, however, is a combination of the repetitiveness of the dysfunctional decision-making process and the persistent and long-lasting effect of the subsequent series of decision-making (See Table 1).

The Death Spiral Effect differs from groupthink, group polarization, and the Abilene paradox in that groupthink, group polarization, and the Abilene paradox are often related to a more finite set of decisions around a single topic or outcome (e.g., the Bay of Pigs invasion) and focus more on group harmony and agreement (Janis, 1972, 1982a,b; Harvey, 1974). Thus, while groupthink, group polarization, and the Abilene paradox are often part of a Death Spiral, a Death Spiral is more prolonged, pervasive, and pathologically dysfunctional behavior, affecting many aspects of the life of a person, a team, a company, or even the entire society. At a certain point, just like in groupthink, self-appointed mind guards appear, but the scale is much greater. The Death Spiral Effect goes one step further and can lead to the collapse of an entire society.

Mass formation has also been offered as an explanation for what is happening in society (Desmet, 2022; Schippers et al., 2022). This theory sees the people in society as a swarm, which will move in one direction, following one narrative. The mass formation concept does not have a 'going around in circles' element, which the Death Spiral has. The vagabond element in this theory states that people do pay attention to the behavior of others and copy that behavior (Bak-Coleman et al., 2021; Desmet, 2022). Swarm dynamics is also studied in research on complex adaptive systems (Huepe et al., 2011). Although mass formation can be part of the Death Spiral Effect, and irrational group behavior is an element of this effect, the Death Spiral provides a broader explanation of what happens when (groups of) people get stuck in this cycle.

The dysfunctional behaviors exhibited in a Death Spiral also include micromanagement, a leadership style that stifles creativity and innovation (Allcorn, 2022) and has been identified as a danger in terms of human freedom and an open society (Esfeld, 2022; see Table 1). "Tit for tat" is a concept from game theory, which is somewhat similar to the Death Spiral effect in that parties get stuck in a behavioral mode, achieving suboptimal results for the parties involved, while it would be possible for the parties to change their behavior (and thereby get better results). The main difference is that the scope of the death spiral effect is much broader, with more far-reaching implications and ripple effects.

2.5 Societies in decline: Death spirals throughout history

Scientists have offered a variety of explanations for the collapse of civilizations in ancient and modern history (Tainter, 1989; Spengler, 1991; Bunce et al., 2009; Scheffer, 2016). Often, a combination of factors can play a role in social decay (Jones, 2021). Yet there are recurring patterns (Jones, 2021). Often, the signs of decay are clear and the decay may have started long before the collapse (Scheffer, 2016). The study of societal collapse, collapsology, has traditionally been studied by historians, anthropologists, and political scientists. Experts in cliodynamics and complex systems have also joined this field, although experts within management and psychology may have a lot to offer in terms of behavioral explanations so far. Similar to the initial phase of decline in companies, societies tend to act too late, resisting change until smooth adjustments have become impossible (Scheffer, 2016). The "sunk cost effect", based on escalation of involvement, prevents people from abandoning and giving up their possessions, lifestyles and beliefs, even when the need to do so becomes clear (Janssen et al., 2003; Scheffer, 2016). Often, elites also have an interest in maintaining the status quo (cf. Pratto et al., 2006; Wilkinson and Pickett R. G., 2009).

From a psychological point of view, trauma, which causes a shift in behavior from functional to dysfunctional, seems to be the key to understanding the Death Spiral Effect. From a biological point of view, collapse can be considered inevitable after a period of high population growth (Downey et al., 2016). As complex systems, common factors can contribute to decline, and these can have ripples or cascading effects (Diamond, 2013). For a long time, the Malthusian catastrophe (the idea that population growth exceeds the (linear) food supply, resulting in mass starvation and death) was seen as a major threat (e.g. Diamond, 2013; Ramya et al., 2020). However, within a complex agricultural system, it seems possible to feed a growing world population. There also seems to be general agreement in the literature that food shortages in the past were not the only cause of societal collapse, and perhaps even a consequence of the inability of societies to cope with their problems (Diamond, 2013). Erosion of established systems and the resulting lack of loyalty to established political institutions plus an increase in inequality are all signs of decline (Turchin, 2007; Diamond, 2013; Van Bavel and Scheffer, 2021). In the interconnected globalized 'system-of-systems', "a failure in one component can lead to a disaster in the entire structure" (Centeno et al., 2022; p. 61). Some see signs that society is on the brink of collapse (Page, 2005) and that, while the scale of the disaster may be unprecedented, the lessons of the past in complex systems are still relevant today (Centeno et al., 2022). Poor institutional choices lead to an inability to solve collective action problems (Page, 2005). It has recently been noted that we are living in a major third power shift in modern history, after the first, the rise of the Western world since the 15th century, and the second, towards the end of the 19th century, the rise of the United States (Peters et al., 2022). The current shift in power is marked by the rise of China, India, Brazil and Russia. A major problem facing the US is not only the growth of economic inequality, which is huge, but also the political division of society, military overreach, and financial crises (Peters et al., 2022). The power elite hold positions that allow them to make decisions that have far-reaching consequences for ordinary men and women. They are also often in a position to influence politicians and pressure groups (Mills, 2018). At the same time, some authors speak of a Netocracy, a global upper class with a power base that stems from technological advances and networking skills. The new underclass, or masses, is Consumtariat whose main activity is consumption, regulated by those in power (Bard and Söderqvist, 2002). What is generally becoming clear in the literature is that increasing inequality, which in fact represents a growing gap between elite and masses, is an important and possibly reversible marker of social decay (Moghaddam, 2010; Diamond, 2019).

2.6 Repeated low-quality decision-making

In a society in decline, the speed of decline and the possible reversal partly depend on the reactions of the government (Toynbee, 1987; Hutton, 2014). In some cases, no action will be taken, if a threat is not seen as requiring urgent action, but equally devastating can be an overreaction to a threat (Maor, 2012; Mar, 2020; Hafsi and Baba, 2022). An action bias, a bias that favors action over doing nothing, often occurs when the incentives to take action are greater than the incentives not to take action (Patt and Zeckhauser, 2000). After a while of ignoring warning signs, a tendency to overreact can take over, and this can also involve suboptimal decision-making (Lorange and Nelson, 1985).

When a crisis is over, decision-makers often don't carefully consider all the pros and cons. Taking these types of actions is more common than taking preventive, anticipatory actions, such as health advice, actions to prevent a health crisis, and actions to prevent an environmental crisis (Patt and Zeckhauser, 2000; Magness and Earle, 2021). In the COVID-19 and associated economic crisis, for example, there are indications of such an action bias (Winsberg et al., 2020; Magness and Earle, 2021, p. 512; Schippers et al., 2022). People often assume that a big problem needs hard and drastic solutions, while less drastic, but precise solutions and targeted, evidence-based interventions may work better than aggressive solutions (cf. Brown and Detterman, 1987; Wilson, 2011; Walton, 2014). Action bias, together with escalation of commitment and sunk cost fallacy may have played a role in the suboptimal decision-making processes surrounding the COVID-19 crisis (Schippers and Rus, 2021). Combined with the (in retrospect) overestimation by experts of the expected infection mortality and of the buffering effects of various aggressive measures (Chin et al., 2021; Ioannidis et al., 2022; Pezzullo et al., 2023), this led to a disastrous chain of self-perpetuating decision-making (Magness and Earle, 2021; Murphy, 2021). Instead of backing down, the overall political climate and response to the measures and to defending a narrative in support of them doubled, leading to a death spiral of low-quality decision-making and dire consequences.

2.7 Main characteristic of social decay: increasing inequality

In today's society, there are a number of clear signs of social decay. While dwindling resources are not always evident in declining societies, a key characteristic is a hierarchical order and an elite with a lot of access to resources while the masses increasingly struggle to survive (Diamond, 2013; Rushkoff, 2022). Recently, a fairly strong increase in inequality has been observed (for an overview see Schippers et al., 2022). This increase is partly driven by wage inequality, which has increased sharply in developing countries over the past 40 years (Acemoğlu and Restrepo, 2021). Wage inequality is largely caused by automation (Acemoğlu and Restrepo, 2021). While poverty has decreased since the 19th century (Sullivan and Hickel, 2023), there are now clear signs that this trend is being reversed. Economic inequality has been found to have a range of effects, such as reduced mental and physical health (Wilkinson and Pickett R., 2009; Pickett and Wilkinson, 2015), declining trust, cooperation and social cohesion in society (Gustavsson and Jordahl, 2008; Elgar and Aitken, 2010; Van de Werfhorst and Salverda, 2012), increasing violence and social unrest (D'Hombres et al., 2012; Jetten et al., 2021) and increasing support for autocratic leadership (Jetten et al., 2021). Increasing inequality can therefore have far-reaching consequences and destabilising effects than is generally assumed, including through the effect on the sociopolitical behaviour of citizens and reduced social cohesion (Van Bavel, 2016; Jetten et al., 2021). Since the global financial crisis of 2008, this trend towards increasing inequality has become more visible (Jetten et al., 2021).

Health within a population progressively deteriorates along with a development of reduced economic equality. Societies with relatively equal income levels also tend to have low stress levels and high levels of trust, and people in such societies tend to be cooperative. In unequal societies, distrust increases because the rich fear the poor and worry about their wealth, while the poor suffer from stress, status anxiety, and bitterness (Wilkinson and Pickett R., 2009; Wilkinson and Pickett R. G., 2009). Health and life expectancy are declining for the poor, the unemployed and the low-skilled (Smith et al., 1990; Marmot and Shipley, 1996; Neckerman and Torche, 2007; Boehm et al., 2011). Importantly, economic inequality has also been described as a downward spiral effect of social problems. These include teenage pregnancies, where babies born to such mothers are at greater risk of educational failure, juvenile delinquency, and becoming teenage parents themselves, with declining health and increasing incarceration of those lowest on the social ladder (Wilkinson and Pickett R., 2009). On a larger scale, societies fall apart and social dysfunction increases when an ever-increasing group of poor is unable to support themselves, let alone earn the money and produce the food to sustain the rich, and the gap between the elite and the masses has become too great to bridge (Wilkinson and Pickett R., 2009, Wilkinson and Pickett R. G., 2009).

Note that while most social problems are greater in unequal countries, suicide rates and smoker rates tend to be higher in contemporary societies with relatively high levels of equality, because aggression and violence are inward-looking and will often be self-centered, as people tend to blame themselves when things aren't going well (Wilkinson and Pickett R., 2009). Inequality can be at the root of many problems in societies and more equal societies do better on almost all fronts (Marmot and Shipley, 1996; Wilkinson and Pickett R., 2009; Boehm et al., 2011).

2.8 Historical examples of increasing inequality and social decay

Before the 19th century, most unskilled workers were able to support a family of four children (Sullivan and Hickel, 2023). A review of wages and mortality since the 16th century showed that extreme poverty was generally not widespread, with the exception of severe social disruption such as war, famine, and institutionalized dispossession. Interestingly, the rise of capitalism initially caused a dramatic decline in human well-being, in terms of a drop in wages below the subsistence level. In several regions, such as northwestern Europe, progress in terms of human well-being did not begin until the 1880s, and in other regions only in the mid-20th century. This period was marked by anti-colonial and social political movements and a redistribution of income, public services, and the welfare state (Sullivan and Hickel, 2023).

If we go back even further, there seems to have been a death spiral during the decline of the Roman Empire. Even when the end was near, instead of trying to address the problems, there was unrealistic and excessive optimism about the future and clinging to the past (Grant, 1976). In the earlier periods of the empire, the elites were willing to sacrifice lives and treasures in the service of the common good, while in the period of decline, the elites became increasingly selfish (Turchin, 2007). This went hand in hand with a decline in cherished values such as thinking for the common good and virtues, larger bureaucracies and an increase in inequality with a sharp increase in the enrichment of the richest 1 percent in Rome and an impoverishment of the middle class (Goldsworthy, 2009).

“(…) The richest 1 percent of Romans during the early Republic were only 10 to 20 times as wealthy as an average Roman citizen. (…) Around 400 AD, just before the collapse of the empire and when the degree of wealth inequality reached its maximum, an average Roman nobleman of senatorial class had assets worth about 20,000 Roman pounds of gold. There was no "middle class" comparable to the small landowners in the third century BC; The vast majority of the population consisted of landless peasants who worked land that belonged to nobles. These farmers had hardly any property, but if we estimate that (very generously) at a tenth of a pound of gold, then the difference in prosperity would be 200,000! Inequality grew both because the rich became richer (late imperial senators were 100 times richer than their Republican predecessors) and because the middle class became poor, and even destitute." (Turchin, 2007; pp. 160-161).

This increase in inequality seems to be an overarching theme in many analyses of the collapse of the empire (Turchin, 2007). Turchin's work describes a series of nested cycles of periods of relative prosperity and abundance, which lead to an increase in population, but also to increasing inequality and dysfunctionality. Inequality affects asabiyya,1 or social cohesion, defined by Turchin as: "the ability of a social group to take collective action collectively" (Turchin, 2007; p. 6). Asabiyya is generally high during times when empires are on the rise and low when empires are in decline (Turchin, 2007). Similar to the "Universe 25" experiment (described in par. 1.1.10), this in turn leads to a collapse of cooperation and precedes a period of scarcity. In the next phase, disease, hunger, violence and war then lead to a rapid decline and often collapse of civilization (Turchin, 2007; see Figure 2).

2.9 COVID-19 crisis and rising inequality

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, some have stated that this is a major leveling and that "we are all in this together", but this is clearly not the case: vulnerable groups have been unequally affected (Ali et al., 2020). Inequality has increased sharply since 2020 (Schippers et al., 2022). Although this trend was already visible before the pandemic started (for an overview see Neckerman and Torche, 2007), the wealth of billionaires in particular increased dramatically early during the crisis (Schippers et al., 2022; Inequality, 2023). Between March 18, 2020, and October 15, 2021, billionaires' total wealth increased by more than 70%, from 2.947 trillion to 5.019 trillion, and the richest five saw their wealth increase by 123 percent. Since then, profits have fallen slightly due to market losses (Collins, 2022). Corporate profits also rose as large companies used the excuse of the crisis to push up the prices of gasoline, food, and other staples (Inequality, 2023). While CEO wages rose, general employee wages lagged behind, widening the pay gap between CEOs and employees in the United States (Inequality, 2023). To prove this, in 2019, the median salary of CEOs was $12,074,288 per year compared to a median annual wage of employees at the 100 largest low-wage employers of $30,416 in the United States; in 2020, the average annual salary of CEOs was 13,936,558 (an increase of 15.42%), for employees it was 30,474 (a meager increase of 0.19%; Inequality, 2023).

In fact, billionaires earned $3.9 trillion worldwide at the end of 2020, while workers' income fell by $3.7 trillion worldwide, as millions worldwide lost their jobs (International Labor Organization, 2020; Berkhout et al., 2021; p. 12). The workers with the lowest incomes were hit hardest. In total, an estimated 150 million people fell into extreme poverty in 2021 during the crisis (Howton, 2020). With the widespread ongoing decline, even the rich may start to lose. The crisis has exacerbated many other aspects of inequality, such as inequalities in education, race, gender and health (Byttebier, 2022; for an overview see Schippers et al., 2022). Despite this, the elite can continue to centralize power and make decisions that are not in the best interest of most people (Desmet, 2022). As the "masses" enter a downward spiral of falling incomes and are unable to afford essentials such as food, gas, and medicine, they may experience significant financial impediments and avoid health care in order to cut costs (Weinick et al., 2005), leading to a deterioration in health status for millions (Schippers et al., 2022). Socioeconomic determinants of health often result from persistent structural and socioeconomic inequalities, exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis (Ali et al., 2020; Schippers, 2020). The term syndemic describes "a set of closely related and mutually reinforcing health conditions that significantly affect the overall health status of a population, against the backdrop of an ongoing pattern of harmful socioeconomic conditions" (Bambra et al., 2020; Byttebier, 2022, p. 1036). Previous pandemic crises such as the Spanish flu and other economic shocks led to an increase in inequality and unequal health and wealth outcomes (Bambra et al., 2020). Sudden economic shocks, such as the collapse of communism, are associated with an increase in morbidity, mental health decline, suicide, increased ill health, and deaths due to substance use (Bambra et al., 2020). These effects were perceived unevenly in poorer regions and among low-skilled workers, exacerbating health inequalities (Bambra et al., 2020). Interestingly, countries that chose not to cut health and social protection budgets after the 2008 financial crisis achieved better results than countries that severely cut these budgets (Stuckler and Basu, 2013; Bambra et al., 2020). In the current time, people lower on the social ladder are most affected by the negative side effects of the measures, in terms of health, lifestyle changes and decrease in income (Schippers et al., 2022), making them even more vulnerable to viral diseases (Enichen et al., 2022).

The dysfunctional situation in most countries worldwide reinforces the incentive for mass migration to Western countries that still offer better prospects, at least in theory. However, if this challenge is mishandled, it can lead to the importation of poverty (Martin, 2009; Murray, 2017), creating an underclass and an unequal society and possibly also a death spiral effect (cf. Gomberg-Muñoz, 2012; Peters and Shin, 2022). Additionally, there is evidence that poverty leads to higher crime rates (Dong et al., 2020). In the US, even petty crimes are severely punished and the incarceration of poor people increases inequality (Wacquant, 2009; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009a).

2.10 Dysfunctional behavior of both elites and masses

Previous research has shown that extreme inequality leads to dysfunctional societies, both in the animal kingdom and in human societies (Grusky and Ku, 2008). In the animal kingdom, extreme inequality has been shown to lead to "behavioural decline" or extremely dysfunctional behaviour (Anderson and Bushman, 2002). In the Universe 25 behavioral experiment, mice lived in perfect conditions with adequate living space, food, and water, but as their numbers increased, inequality increased, and the behavior of all mice became dysfunctional and led to the extinction of the colony, long before the maximum number of mice was reached (Calhoun, 1973; Adams and Ramsden, 2011). It is claimed that in that particular experiment, where resources were plentiful, the control of resources by a small number of mice, as well as excessive (negative) interaction led to the demise of the colony (Ramsden, 2011). Even after the numbers dropped below the level at which pathology began, the mice's behavior remained dysfunctional (Ramsden and Adams, 2009). The extent to which these studies are valid for human society is certainly debatable. For example, for obvious ethical reasons, it is not possible to do a study in which some form of extreme hierarchy is tested and then abolished, but there is general agreement that countries with high inequality have more social problems (Grusky and Ku, 2008; Van Bavel, 2016).

Historically, the elite that accelerates problematic societal developments and is often at the beginning of the Death Spiral Effect, because of their greed and hunger for power, or simply because power corrupts, also becomes fearful as societal decay progresses (Baker, 2022; Rushkoff, 2022). The pressure to sustain economic growth comes with repercussions and an inevitable erosion of the financial markets, as happened in 2008, for example (Rushkoff, 2009). Rushkoff (2009) had hoped that there would be a self-correcting mechanism when financial markets collapse, but this was apparently not the case. When the elite notice that things are going wrong, they often use their wealth not to make things better, but to protect themselves from the "masses" and for "escapism". They look for ways to escape the impending societal collapse they helped create (Rushkoff, 2022). While the masses experience a loss of freedom and prosperity and desperately try to hold on to the possessions and resources they still have (desperate principle; Hobfoll et al., 2018), the elite also realize that fate can strike and they can also end up in a survival mode and even start fighting each other (cf. Turchin, 2007).

At the moment, optimism about connectivity and the internet and the possibilities for open source democracy seems to have faded (Rushkoff, 2003). Censorship has made its appearance, along with a loss of scientific freedom (Da Silva, 2021; Kaufmann, 2021; Shir-Raz et al., 2022). Scientific debate was stifled during the COVID-19 crisis and dissenting views were censored (Shir-Raz et al., 2022). Suppression tactics resulted in damaging careers of dissenting physicians and scientists, regardless of their academic or medical status (Shir-Raz et al., 2022). This has led to a loss of trust in science and institutions (Hamilton and Safford, 2021). Worse, when well-informed scientists are suppressed with reasonable arguments and rigorous data, it can provide conspiracy theorists with ammunition to argue that orthodox science is bigoted and wrong. Centralized censorship, in particular, can increase the certainty of radicalized views (Lane et al., 2021). Anyone who questions "the science" and official government narratives can be called a conspiracy theorist, as a way to discredit and delegitimize critics (Giry and Gürpınar, 2020). It has been argued that conspiracy theories are also a sign of dissatisfaction with governance, society, or policy, and some conspiracy theories may turn out to be true (Swami and Furnham, 2014).

Surveillance capitalism, the collection and trading of personal data by companies, shifts power from governments to large corporations (Big Other). These companies have the power to observe and influence human thought and decision-making, for example through direct advertising. Direct advertising has become much more aggressive (Schwartz and Woloshin, 2019), especially for products with little benefit and high sales (DiStefano et al., 2023). Effective direct advertising can be driven by surveillance capitalism. This can be a tool for companies (knowing customer preferences), but also an invasion of privacy (Zuboff, 2015, 2023, see also Yeung, 2018). Worryingly, strategic actors such as large corporations and governments (i.e., the elite) may influence the media unequally (media bias), potentially leading to an increasingly narrow definition of "facts/true knowledge" versus "fake news/disinformation," for example, by stating that only government or other elite-backed narratives can influence the media. (cf. Gehlbach and Sonin, 2014). People and scholars who deviate in their views from the official narrative can be censored, marginalized, and ostracized, even if they are cautious in their publications and wording within the debate (cf. Prasad and Ioannidis, 2022). Some authors have even argued that this combination can put us on the path to totalitarianism (Desmet, 2022), and have called for a way to rethink and uphold democracy and democratic principles (Della Porta, 2021; Ioannidis and Schippers, 2022), as well as democratic control over technology (Gould, 1990).

A more positive solution such as a form of direct democracy is often not considered and when it is, people often feel unable to bring it about (cf. Rushkoff, 2019). In general, distrust escalates under such conditions because the elite begins to fear the masses and the masses become afraid of the elite and both tend to engage in dysfunctional behavior (cf. Widmann, 2022). In phase 4 (Figure 2), when resources are dwindling as a result of the continuous downward spiral, the desperate principle may apply. The desperate principle is formulated within the conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll et al., 2018). In COR theory, people, organizations and societies strive to obtain and retain resources that they value. Because the loss of resources is more salient than the extraction of resources, people go to great lengths to prevent the loss of resources. However, individuals and groups must invest resources to prevent resource loss, recover from losses, and/or gain resources. When valuable resources are lost, resource extraction becomes more important (Hobfoll et al., 2018). The desperation principle states that "when people's resources become depleted or depleted, they enter a defensive mode to preserve the self, which is often defensive, aggressive and can become irrational" (Hobfoll et al., 2018, p. 106). Resource loss cycles indicate that stress and a cycle of faulty decision-making can lead to fewer resources to compensate for resource loss and these loss spirals "increase in both momentum and magnitude." At the same time, "profit spirals are generally weak and develop slowly" (Hobfoll et al., 2018, p. 106). This indicates that once this spiral is deployed, it is difficult to reverse, and the death spiral effect can occur.

3 Reversing the downward spiral: upward spiral

3.1 Breaking Free: Strategies to Overcome Societal Dysfunctional Behavior

In general, major societal challenges such as rising inequality, social unrest and societal decay affect large parts of the population, are very important, but potentially solvable (Eisenhardt et al., 2016). Recently, management scholars have applied organizational knowledge to a societal context by formulating solutions to such societal challenges using management theories (George et al., 2016), and models have been offered to integrate resilience literature with crisis management literature (Williams et al., 2017). For example, scientists have proposed solutions for alleviating poverty (e.g. Banerjee and Duflo, 2011; Mair et al., 2016) and psychological injury in the context of major conflicts and wars (De Rond and Lok, 2016). With regard to reducing inequality, the work of Mair et al. (2016) may be particularly interesting, as they propose propositions as a way to reduce inequality and alleviate poverty. A downward spiral can be reversed by using an adaptive response. This can be important to reverse the trend, but also in the case of recovery after a collapse (cf. Bunce et al., 2009). Based on the above literature, the following steps may be necessary

Ensuring that those involved also participate in the decision-making process is essential. As Perret et al. (2020): 1 state: "The fate of states, corporations, and organizations is shaped by their decisions. It is surprising, then, that only a minority of individuals are involved in the decision-making process." This would suggest that a rigorous change in the way societal decisions are made may be an important point to intervene (Lupia and Matsusaka, 2004; Demarest and Victor, 2022). In general, the upward spiral can start with (1) an open attitude towards changes that are necessary to break the downward spiral. These can include (2) reflection on the current and desired situation, as well as (3) the development of a strategy for restoring trust, rather than a focus on finding scapegoats (e.g., avoiding a blame game can be achieved through a truth and reconciliation commission), and (4) involvement of more members of society. This can lead to (5) better quality decision-making and more autonomy and positive ripple effects within society, and this in turn can lead to (6) less social inequality and (7) a freer and more open society where people can thrive and flourish. Coming back from setbacks requires both resilience and compassion, as described below.

3.2 Resilience

The concept of resilience, or how individuals, organizations, and societies bounce back from adversity, is informational (Van Der Vegt et al., 2015), and this is also mentioned as an important concept within models of complex adaptive systems (e.g., Centeno et al., 2022). Resilience at all levels seems to depend on social integration, for example on how supportive families and communities are, and this is especially evident in times of crises (Banerjee and Duflo, 2011; Van Der Vegt et al., 2015). Having resilient networks is also important in this regard, and research on strengthening networks and communities can be key to societal resilience and rebuilding society after decline has set in (Van Der Vegt et al., 2015). Trust and compassion, as well as effective communication and collaboration within networks can not only enable a more effective response to crises and disasters (Shepherd and Williams, 2014), but also reduce the suffering caused by societal decay (Williams and Shepherd, 2017). After disasters, such as earthquakes, family businesses, especially those involving more members, have been found to be best able to take advantage of post-traumatic entrepreneurial opportunities for recovery and growth (Salvato et al., 2020). Recent work in a corporate context has shown that companies can respond to adverse events in different ways to overcome post-shock challenges (Shepherd and Williams, 2022). This research highlights the role of post-adversity growth during adversity and provides insight into the different paths to resilience. This research offers insights into how you can break a death spiral and move into an upward spiral.

3.3 Compassion

Because a downward spiral is often accompanied by a loss of humanity, reversing the downward trend requires a restoration of humanity and compassion. Compassion organizing was coined as a term to describe the coordinated organizational response to human suffering inside and outside the organization (Dutton et al., 2006). Compassion is an innate response to human suffering and includes the acknowledgment of suffering, empathic concern, and behaviors aimed at alleviating suffering (Dutton et al., 2006). Reversing a downward trend of societal decline can be more difficult than post-traumatic growth after (natural) disasters, if only because of their magnitude. While a disaster can encourage compassionate organizing to alleviate mass suffering (Shepherd and Williams, 2014; Williams and Shepherd, 2017), what can be done to alleviate suffering and crisis management in the context of societal downturn may be less obvious (cf. Williams et al., 2017). Often, individuals, teams, and organizations working to alleviate suffering experience intense emotions that can elicit strong commitment from volunteers and businesses, and people often refer to this as a "calling" (De Rond and Lok, 2016; Schabram and Maitlis, 2017; Langenbusch, 2020). However, this sensemaking and strong emotion can also lead to wrong decision-making (Cornelissen et al., 2014; Hafsi and Baba, 2022). In the COVID-19 crisis, digital innovations were proposed as a way to alleviate suffering (Majchrzak and Shepherd, 2021). However, we need rigorous studies on which compassion-based interventions can be effective. It is important to help people regain meaning in life and increase post-traumatic growth of individuals and groups in society (De Jong et al., 2020; Dekker et al., 2020).

3.4 Turnaround leadership and culture change

Previous research has shown that leadership is key to follower behavior (Cao et al., 2022). Passive and destructive leadership styles, such as abusive, narcissistic, and authoritarian, were associated with higher levels of dysfunctional follower behavior, i.e., aggression in the workplace. Conversely, ethical leadership, change-oriented and relationally oriented leadership was negatively associated with aggression in the workplace. If the behavior of leaders changes, this also affects the organizational culture and the behavior of followers.

A historic turnaround leader who managed to get a country out of a negative spiral was Nelson Mandela, in South Africa. Instead of installing tribunals, he set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This helped to get past the question of guilt and to regain respect for each other. One problem with leaders rising up in turbulent times is that in the midst of the turmoil, they are often not recognized and appreciated by the masses and they can also be seen as enemies of the ruling elite. If they try to reverse the downward spiral, they may face hardship, imprisonment, and sometimes even death. Nelson Mandela, for example, spent more than 27 years in prison.

Turnaround leadership faces the difficult task of breaking the negative spiral, restoring trust and bringing back positive energy within the organization (Bibeault, 1981) or society (Gibson, 2006). This is all the more difficult because such companies often suffer from collective denial, or unwillingness to admit that there is a problem at all. Sometimes the problems become so big that people pretend that the problem does not exist (see Meyer and Kunreuther, 2017). At the company level, it has been established that while individuals know and may even admit that the company is in trouble, they collude in collective denial, or pluralistic ignorance (Kanter, 2003). Strategies that successful turnaround leaders in companies often use are to promote dialogue, generate respect, encourage cooperation and inspire initiative (Kanter, 2003). The challenge is to what extent the tactics used by a turnaround leader within an organization can also be applied at a societal level. Without a shared vision, recovery after collapse in the context of adaptive systems is unlikely (Bunce et al., 2009).

3.5 Avoiding blame game

During the COVID-19 crisis, many people began to suspect that conspiracies were at play, probably due to both the scale of the events and the need for explanations (Van Bavel et al., 2020; Douglas, 2021; Pummerer et al., 2021; Ivanova, 2022). While belief in conspiracy theories has been associated with reduced institutional trust, less support for and compliance with imposed measures (Pummerer et al., 2021), it can also be seen as an ineffective form of dealing with the situation (Schippers, 2020). While people may feel the need to find out who or what is to blame for the situation, the dangers of co-occurring collective narcissism (i.e., exaggerated belief in the greatness of the in-group, which is not recognized by others) and conspiracy theories, such as endorsing violence and undemocratic governance (De Zavala et al., 2022). Because the relevance and/or veracity of conspiracy theories are often difficult to verify, constructive ways of making progress are often blocked when they are rampant. When we focus on parties at fault for the situation, some people feel that revenge can be useful, but guilt usually fulfills a felt need for retribution and only a subset of people seem to find revenge important and even enjoyable (Szymaniak et al., 2023). Punishment of offenders is not very effective in preventing or reducing violations in terms of law enforcement (Metz, 2022). In the current situation, this can be even more complicated, as a lot of damage may have been done for the "right" reasons, namely in the name of public health (Schippers and Rus, 2021; Schippers et al., 2022). It can be difficult to disentangle the motivations of individual decision-makers and decisions were also taken in a context of adoption of such measures (cf. Ohlin, 2007). A more constructive approach can therefore lie in reconciliation (Metz, 2022), reversing the most aggressive and ineffective policies, and learning from mistakes to do better in the future (Schippers et al., 2022). However, if the pressure to retaliate and demand retribution escalates, policymakers who have made serious mistakes are likely to work twice as hard to avoid punishment. As many of these policymakers continue to hold power in (or over) public health and science, such defensive continued endorsement of false narratives can be devastating to the credibility of both public health and science at large. In addition, it is necessary for people to be able to easily experience positive emotions instead of stress (Johnson, 2022). Preventing long-term stress is crucial for quality of life and longevity (Johnson, 2022). Mutual empathy may need to be fostered in generating a positive outlook for the future (Beck et al., 2018; Halamová et al., 2022).

3.6 Civil and intelligent disobedience

Whether in families, groups, organizations, or society, when people perceive that a toxic culture is ingrained or becoming visible, most people struggle to address it, for fear of being excluded from the group, or because they don't know how to reverse the downward trend (Packer, 2009; Richardson, 2020). Richardson (2020) describes that with a change in society to a "new normal", people with power will demand obedience. Concentration of power and wealth at the top is often accompanied by the enforcement of obedience to new habits, rules and behavior. In the early stages, people often downplay the signs of danger and give in to coercion, fearing the consequences (Richardson, 2020). People who openly resist or criticize decisions often face serious consequences. Effective ways of "resistance" listed by Richardson (2020) include a refusal to accept the new imposed goals and tradition, not believing that this new order is inevitable, and making a conscious choice to "stay behind" rather than participate. All this while maintaining civility and commitment to the common good, and adhering to values that are important for a civil society (Richardson, 2020). Constructive deviation and speaking up (as opposed to silence) are an important step in countering (organizational) abuses (Starystach and Höly, 2021). Also, civil and intelligent disobedience can be ways to counter actions chosen by leaders and policymakers that can harm society or businesses as a whole (Chaleff, 2015; Hughes and Burnes, 2023). Some even argue that constructive deviance and intelligent disobedience should become socially expected behavior (Ralston, 2010). This is in line with recommendations to prevent groupthink by appointing a "devil's advocate" (Janis, 1982b; Janis, 1983; MacDougall and Baum, 1997; Akhmad et al., 2020). Interestingly, group members who strongly identify with the group are more likely to speak out about collective problems (Packer, 2009). Another action that individuals and groups can take is high-quality listening, as an antidote to polarization, a huge problem in society (Itzchakov et al., 2023; Santoro and Markus, 2023). Recent research shows that truly listening to understand the other person's perspective can help with depolarization and be a valuable tool for bridging attitudinal and ideological gaps (Itzchakov et al., 2023; p. 1).

3.7 Collective action

In addition to individuals in groups and societies making their voices heard and voicing their concerns, collective action can have other benefits. While individual control over the social system may seem out of reach, collective action can produce positive outcomes for the group as a whole (Klandermans, 1997). Key predictors of collective action are perceived injustice, effectiveness (i.e., sense of control), and identity (i.e., identification with a group; Van Zomeren et al., 2008; Van Zomeren, 2013). People are also more likely to participate in protests if they see injustice for the group they identify with (Klandermans, 2002). Injustice and effectiveness appear to be stronger predictors of collective action in the case of incidental rather than structural disadvantages, while group identification was a strong predictor of collective action for both types of groups (Kraemer, 2021). While structural deprivations are more harmful, both psychologically and in terms of inequality, they are less likely to elicit action-oriented emotional response and collective action (Major, 1994; Schmitt and Branscombe, 2002), and are therefore more difficult to change (Sidanius and Pratto, 2000; Jost and Major, 2001; Sidanius et al., 2004). Such differences and structural injustices often become ingrained, and disadvantaged groups may even come to regard their condition as natural and unchangeable (Major, 1994). It is then seen as a characteristic of a certain group (Kraemer, 2021) and the existing differences between groups are seen as legitimate (Jost and Major, 2001).

Social Dominance Theory attempts to explain how and why social inequalities based on groups exist and continue to exist, even though people would like a more equal society (Pratto, 1999; Pratto et al., 2006). In most societies, some groups have material and symbolic resources, such as political power, wealth, and access to housing and food (Pratto et al., 2006). Both privileged and disadvantaged groups can come to see the status quo as legitimate and this is often institutionalized. Financial institutions that seek profit maximization, homeland security organizations, and criminal justice systems can strengthen the hierarchy (Pratto et al., 2006). Conversely, human rights and civil rights movements and institutions, welfare organizations, and religious organizations can reduce hierarchy. However, such organisations often lack funding and often do not really challenge the status quo (Pratto et al., 2006). When collective action is taken against the status quo, it is often seen as illegitimate and shut down (Pratto et al., 2006), unfortunately repression of social movements is very common (Loadenthal, 2016). Historically, nonviolent collective actions have been more successful than violent actions to (re)establish democracy (Chenoweth and Stephan, 2008; Chenoweth, 2021), and these types of actions are becoming more common (Kraemer, 2021, see also Schippers et al., 2022). Breaking the downward spiral is therefore not easy and is often jeopardized by the ruling elite.

3.8 Top priority: reducing inequalities

Since we have argued that a (large) increase in inequality is an important marker of societal decay, this issue seems to be of utmost importance to address. Figure 3 shows how this can be done. In the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, SDG10 is about reducing inequality (United Nations, 2022). However, the focus of the goals and indicators seems to be more on improving inclusion than on explicitly reducing inequality (Fukuda-Parr, 2019). This is a significant omission, as it would be critical to address the problem of extreme inequality and the concentration of wealth at the top (Fukuda-Parr, 2019). While our research clearly shows that rising inequality and increasing authoritarianism can contribute to significant societal decline and high mortality rates through the Triangle of Death (disease, famine, and war), it is not easy to determine where to start to reverse this trend. While this may seem like a big and complex problem, when thinking of possible solutions, it's clear that effectiveness and ease of implementation are the most important. Communities have a responsibility to explore methods to address the social, educational, physical, and mental health crisis. Interventions should be rigorously tested with randomized controlled trials for effectiveness and then monitored for their implementation success. At the same time, full equality should not be something to strive for, as it could kill innovation and creativity. Instead, an optimal level of income disparities is important (Charles-Coll, 2010). Indeed, there seems to be an optimal level of (in)equality, with an inverted U-shaped relationship (Charles-Coll, 2010). In situations where ordinary people are involved in shaping the response to a crisis, a further increase in inequality seems to have been prevented (Van Bavel and Scheffer, 2021), and therefore this seems a promising path forward.

The COVID-19 crisis and measures of unprecedented severity and duration are related to many negative side effects and increase inequality worldwide (Marmot and Allen, 2020); therefore, stress, health, and trauma for vulnerable populations must be addressed (Whitehead and Torossian, 2020). It can take a long time to recover from the economic fallout and the increase in inequality (Whitehead and Torossian, 2020). In the coming years, governments must take individual and social well-being as a spearhead in decision-making (Frijters et al., 2020). Hopefully, effective interventions can turn the tide and induce a virtuous circle (e.g., Schippers and Ziegler, 2023). But while many ideas and proposals may emerge, their implementation without rigorous testing can create even more waste after we have already approved too many failed interventions.

4 Concluding Remarks