In this article, Professor Desmet mentions a few interesting concepts from (mass) psychology.

My selection:

- Mass formation: "what one thinks does not matter, what matters is that one thinks it together."

- Mass formation resembles hypnosis: all attention is drawn to one point and consciousness narrows.

- De Takeaway: "But there is also an important difference between mass formation and hypnosis. In hypnosis, only the field of consciousness of the hypnotized person is narrowed; The one who speaks the hypnotic story (the hypnotist) is 'awake'. In mass formation, the person who articulates the story – in this crisis the expert – is also mentally in the grip of the story. What's more, the virologist's field of attention is even narrower than that of the population because of his training (which is one-sidedly focused on viruses) and because of the secondary advantages that the story brings him (excessive prestige, authority, research funding, etc.). This explains the surprising observation that experts make mistakes that a layman would not easily make (a phenomenon sometimes called 'expert blindness')."

The whole article:

'In the corona crisis, public opinion is in the grip of absurd judgments'

Professor of Clinical Psychology at Ghent University.

Professor of clinical psychology Mattias Desmet (Ghent University) explains why a large part of the population during the corona crisis is remarkably easy to accept measures that 'cut' deeply into their pleasure, freedom and prosperity.

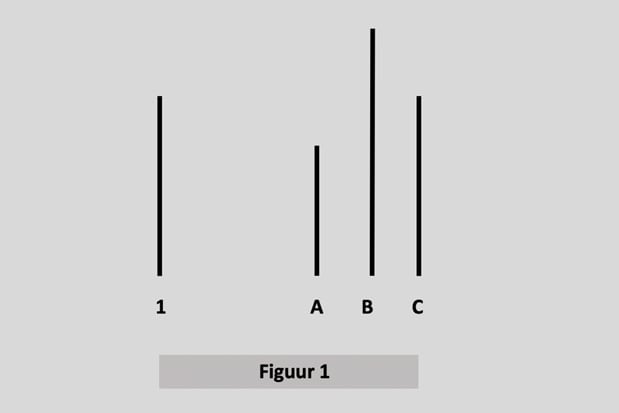

Take a good look at the figure below. Which of the line segments A, B and C is the same length as line segment 1? That was the question that the American psychologist Solomon Asch asked the participants of his experiment on peer pressure. In each group of eight test subjects, there were seven employees of Asch. They all answered 'line segment B' without batting an eyelid.

The eighth participant – the only real subject – gave mostly the same answer as his predecessors. Only 25 percent consistently expressed what even a blind person can see: not line segment B but line segment C is the same length as line segment 1.

After the experiment, some test subjects said that they did know the right answer but did not dare to go against the group. Even more interestingly, others admitted that they had begun to doubt their own judgment under pressure from the group and eventually accepted the absurd group judgment as true.

We have to face it: even in the corona crisis, public opinion is in the grip of absurd judgments. The most famous example is, of course, thatthe reported number of corona deaths in residential care centres was far too high because all deaths were counted,But many other reported figures, such as the infection rate and the reproduction number, were also unrealistic.

However wrong they may be, such messages shape public opinion. They are put forward by experts, often on national television, making it seem as if they are widely accepted. Just as in Asch's experiment, this is sufficient proof of correctness for many people: 'It can't be that everyone is wrong', 'They wouldn't say it if there is nothing wrong with it', etc.

A number of questions arise here: why is a message that is carried by a crowd, even if it is not correct, so convincing? How do intelligent people – the experts – come to send such questionable messages into the world? What dangers are associated with such mass psychological phenomena and how should we deal with them as a society?

In the corona crisis, public opinion is gripped by absurd judgments.

Mass formation often arises in a social climate saturated with unease, fear and lack of meaning (see, for example, the 300 million doses of antidepressants per year in Belgium and the burnout epidemic). In such an atmosphere, the population is extremely sensitive to stories that identify the cause of their fear and thus create a common enemy – the virus – which must then be 'destroyed'.

This yields psychological gains. First of all, the fear that was previously indefinably present in society now becomes very concrete and therefore more manageable mentally.

Secondly, the disintegrating society finds in the common struggle with 'the enemy' a minimum coherence, energy and meaning; The fight against corona will be one laden with pathos and group heroismmission.

Narrowed

In more extreme cases, this puts society in a kind of intoxication that also occurs in a crowd that sings together or chants slogans (e.g. in a football stadium). The voice of the individual dissolves into the overwhelmingly vibrating group voice; The individual feels carried by the masses and 'inherits' its sizzling energy. It doesn't matter exactly what is being sung; What counts is that onetogetherSings. Asch's experiment shows the cognitive version of this: what one thinks does not matter, what counts is that one thinks it.togetherThink.

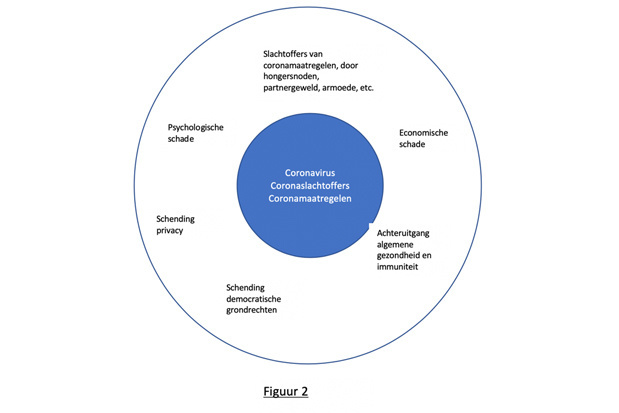

As Gustave Le Bon, a French sociologist, pointed out around 1900, the effect of mass formation resembles that of hypnosis.In both cases, a scary story sucks up all the attention and narrows the field of consciousness. Compare it to the circle of light of a lamp that shrinks and makes everything that falls outside it disappear into darkness (see figure).

In the corona crisis, for example, you can see this in this: victims who fall due to the measures (e.g.deaths from emotional and physical neglect in residential care homes,non-corona patientswhose treatment has been postponed, victims of aggression in the home, etc. receive, at least compared to corona victims, hardly any attention and empathy (no daily statistics, case descriptions, testimonies of family members, etc.) from these victims. They fall outside the circle of light.

This lack of empathy should not be confused with vulgar selfishness.Le Bon noted that both mass formation and hypnosis allow individuals to radically ignore their selfish aspirations, yes, even their own pain.Witha simple hypnotic procedurepatients can be sedated in such a way that incisions can be made without any problems during operations. In the same way, during the corona crisis, a large part of the population is remarkably easy to accept measures that 'cut' deeply into their pleasure, freedom and prosperity.

But there is also an importantdifferencebetween mass formation and hypnosis. In hypnosis, only the field of consciousness of the hypnotized person is narrowed; The one who speaks the hypnotic story (the hypnotist) is 'awake'. In mass formation, the person who articulates the story – in this crisis the expert – is also mentally in the grip of the story. What's more, the virologist's field of attention is even narrower than that of the population because of his training (which is one-sidedly focused on viruses) and because of the secondary advantages that the story brings him (excessive prestige, authority, research funding, etc.). This explains the surprising observation that experts make mistakes that a layman would not easily make (a phenomenon that sometimes occurs).'Expert blindness'is mentioned).

Those who fanatically trust the experts and those who completely distrust them (and see them as conspirators) may therefore make the same mistake here: they attribute to the experts a too absolute knowledge (and power), the first group in a positive sense, the second in a negative way. The real masters of the situation are not the experts, but the stories and their underlying ideologies; The stories belong to everyone and belong to no one; Everyone plays a role in it, no one knows the full script (alsoall American heroBill Gates doesn't).

Mass formation ensures that the shared social narrative becomes immune to criticism and confirms itself to the point of absurdity. For example: In a paradoxical way, the victims who fall through the measures (e.g.due to loneliness in residential care centres) as a pre-measure argument in favour of the measures. They are innocently added to the general excess mortality and thus used to measure thejustify.

The UN warned that famines as a result of the lockdowns could soon cause millions of victims.We run the risk that these too will be wrongly counted among the corona victims and that the fear and therefore the support for stricter measures will increase exponentially. In this way, society can end up in a vicious circle: the stricter the measures, the more victims; The more victims, the stricter the measures.

Society risks ending up in a vicious circle: the stricter the measures, the more victims; The more victims, the stricter the measures.

Don't underestimate what this can lead to in the future. The idea that has been put forward aboutplacing infected individuals in isolation centresis still considered a 'disproportionate' measure. But to the extent that society remains mentally glued to a narrow virological story, it only takes a rise in fear to consider this as 'necessary for public health'.

In combination with the manipulability of corona tests and a feudal redistribution of power (governors and mayors are given unprecedented power due to the impasse of national politics), you can see what appears on the horizon: arbitrarily arresting, isolating and 'treating' 'infected' people. Social systems that tend towards totalitarianism use a different discourse, but they all do more or less the same thing.

The mass psychological dynamics that are emerging around the real core of the corona epidemic show all the characteristics of a psychologicalsymptomand should be analysed as such. Just like an individual symptom, it has asignal function. It refers to an underlying social problem, which we have described above as a lack of meaning and associated epidemic anxiety and depression.

This can be felt in the workplace, among other things. Now that the lockdown and the associated leave (which didn't really feel like a leave) are almost behind us, we have to slowly return to the old work regime. Many of us will once again be confronted with the experience described in the bestsellerBullshit JobsThe working day seems to be a succession of obligations that one has to fulfill without knowing who is actually benefiting from it.

As someone said to me recently, you would almost long for another lockdown. For quite a few people, this seems to be the only way to escape the exhaustingrat raceAnd at least in the fight against the virus, to experience some meaningfulness and connection with the other. Thus, in the current mass formation, we find another characteristic of psychological symptoms: they are attempts to solve the underlying problem ... which are detrimental in the long run.

This is the task we face: to find meaning and connection in life without the need for a war with a virus. Where in our Western worldview is there an opening that offers the prospect of a meaningful existence as a human being?

In this article, Professor Desmet mentions a few interesting concepts from (mass) psychology. My selection: -...

Posted By Anton Theunissen onFriday, September 4, 2020