How does a killer virus with a contagiousness presented as frightening manage to stay under the radar for two months?

Carnival was a super spreading mega-event. It supports the aerosol story.

Camp aerosols

At the time, we didn't expect much harm from carnival because aerosols have hardly any influence. So it must have been a less contagious variant of the virus until then.

Camp RIVM

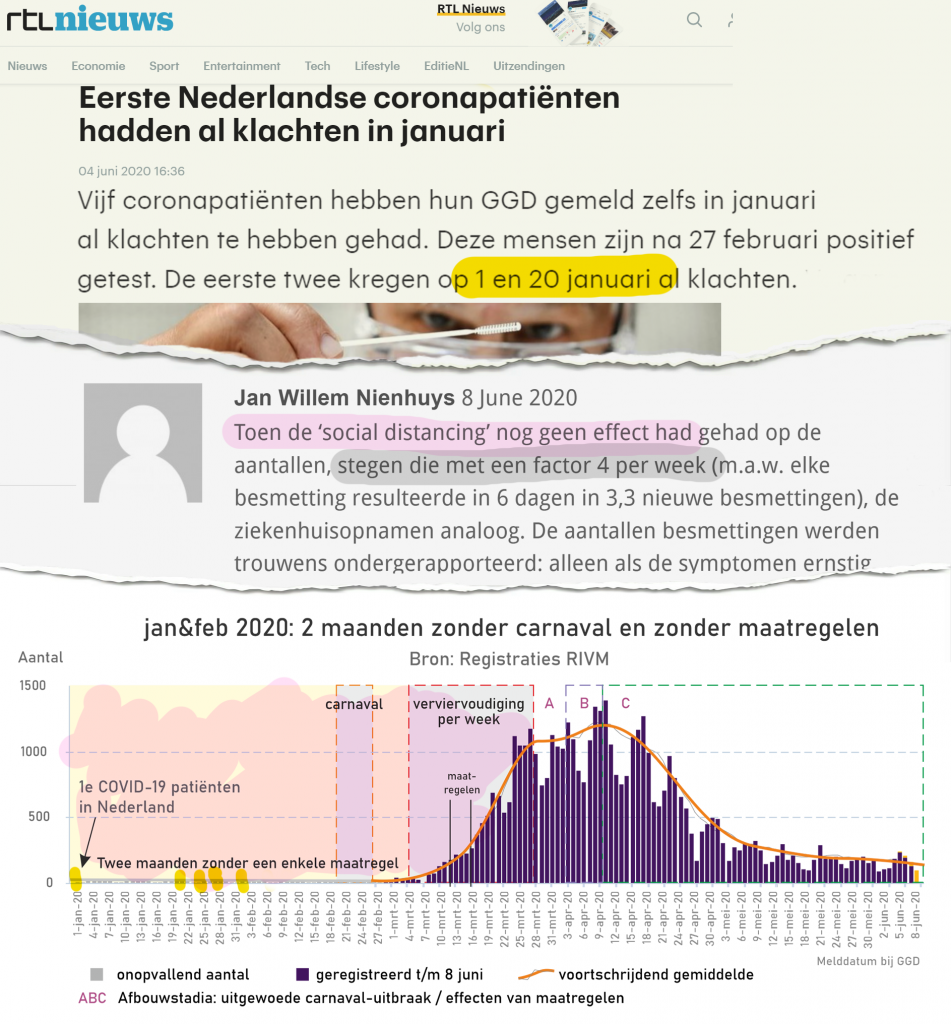

The corona virus had been in our country since January, it turned out recently. The first patient (who tested positive afterwards) even claims to have had symptoms on January 1. Given the incubation period, it should therefore be infected around or before Christmas. Experts consider that chance nil β but the man then just had the symptoms and later turned out to be positive. It may be that the test was false positive, but I don't assume that they just left it at that, because this is a very crazy one. But who knows: the RIVM will report it, so let's just take it for fun.

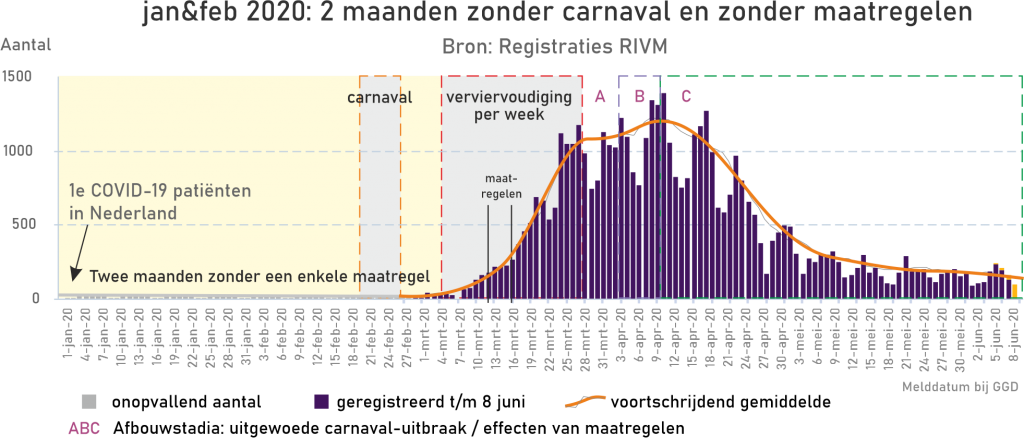

OK, so on January 1 the first corona patient in the country. Later in January and also in February there are already more cases, it concerns a total of several hundred in two months, as far as is known now. According to the R0 theory, there should have been about 500,000 and that would have been noticed: then there would have been a striking number of deaths. That did not happen.

For example, the exponential growth is set by a leading scientist (also highly respected by me) at per 3.3 new infections per corona carrier in every 6 days. That is a fourfold increase in infections every week. This means that by the end of March, when we were waiting for the lockdown effects, there must have been 17 million infections. (Now 3.3 per 6 days seems a bit much to me, but I'll leave that to the respected expert.)

A doubling of the cases per 3 to 4 days is not surprising because we also saw that trend in the mortality rates at a certain point. But even with a doubling every 5 days, starting a week earlier or later, my problem remains:

An infection at the beginning of January, a fourfold increase per week and a lockdown after only 10 weeks while 3% of the population is infected by then - that really does not match. You are talking about at least 4 million infections, if you calculate leniently. And just as easily 16 million (that only saves 1 week).

I have asked here and there what is wrong with my train of thought because I can't get any further. Two answers so far. The first:

OK, I knew my place. It may also be a silly question, but I would like to know anyway.

Another answer was more substantive, I'll summarize because it's a long narrow screenshot: I hadn't taken into account the incubation period because it slows down the doubling time.

I honestly didn't understand that, so I asked why it's called doubling time and if he had any new information about not being contagious during the incubation period, because otherwise it doesn't matter anyway. Heard nothing more about it. I also suspect: too tiring.

RIVM estimated the R0 at at least 2 at one point: with each infection, an average of two (slightly more) people are infected. I can't imagine that either. How can you walk around with the virus for a week to a week and a half and only infect two people? How does that work in practice? So then there are an average of 7 days that you are contagious but do not infect anyone. Is that virus really that contagious?

But maybe most people don't infect anyone at all and others grab a whole hossing room at the same time. That is in line with other theories, but I just can't get them to sell and I'm not the only one. However, more and more studies are appearing that point to the skewed distribution of numbers of infections. 80% is infected by 10%, is about the idea.

I digress. My question remains: How does a killer virus with a contagiousness presented as frightening manage to stay under the radar for two months?