The article below is an adaptation of a part of the CBS report Gezondheid in coronatijd (cbs.nl). Virusvaria hecht groot belang aan het thema ‘oversterfte’. De toelichting van het CBS is echter van dien aard dat de eindredactie van virusvaria enkele correcties heeft moeten aanbrengen alvorens haar lezers hierover te informeren. Uiteraard op basis van exact hetzelfde cijfermateriaal. Wat u hieronder leest is dus niet de uitleg van het CBS maar een analyse van de cijfers door virusvaria. Leg beide stukken gerust naast elkaar om de verschillen te zien en oordeel zelf.

De coronacrisis is naast een beleidscrisis ook een gezondheids- en informatiecrisis. De angst voor een pandemie houdt de wereld nu al bijna twee jaar in haar greep. Beleidsmakers en gezondheidsadviseurs beklagen zich over het feit dat het cijfer dat zij zelf tot kencijfer hebben verheven, niet bekend is. Hun kencijfer is weten “hoeveel mensen zijn er besmet of zijn er besmet geweest”. Dit blijft een bron van discussie, ondanks dat besmettingen al geruime tijd geen correlatie meer hebben met druk op de zorg, ernstige ziekte of sterfte. Het ‘besmettingscijfer’ hangt voornamelijk af van het aantal mensen dat is getest. Dit kan per land, per regio en in de tijd sterk verschillen. Ook geeft een positieve test wel aan of iemand in contact is geweest met het virus maar niet of iemand ‘geïnfecteerd’ is, laat staan of die persoon er ziek van wordt. (Denk aan een voorwerp: een tafeloppervlak kan ook ‘besmet’ zijn maar wordt er niet ziek van en hoeft ook niet ‘besmettelijk’ te zijn.). Om precies te weten hoeveel mensen zijn overleden aan COVID-19, kijken we naar de doodsoorzaak. De oversterfte geeft dus geen enkele indicatie van hoeveel mensen door respectievelijk corona, de vaccinaties of gevolgen van de lockdowns en andere maatregelen zijn overleden. Vanuit die optiek volgt hieronder toelichting op de sterftecijfers.

Oversterfte door corona, maatregelen en/of vaccinaties

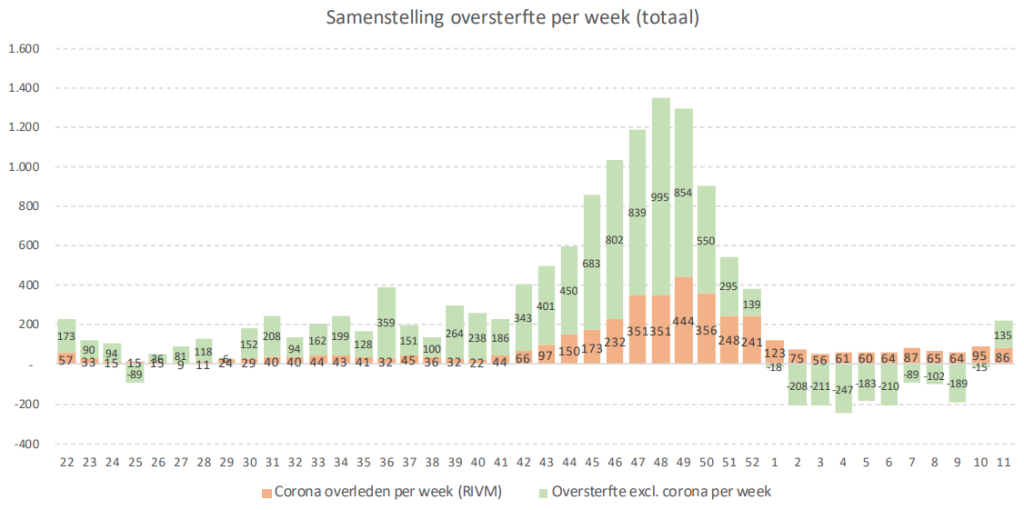

In de koude maanden van het jaar (ruwweg van half november tot half april) sterven er gemiddeld meer mensen dan in de rest van het jaar. Als er sprake is van kou of er komt veel griep voor dan stijgt de sterfte boven de ‘normale’ sterfte uit. Men spreekt dan van oversterfte. Dit gebeurde bijvoorbeeld in 2018, toen een lang durende griepepidemie plaatsvond. In achttien weken tijd overleden er door de griep ruim 2.500 mensen meer dan wat de laatste vijf jaar normaal is voor die periode (‘normaal’ is 6.500 meer dan verwacht). Na een periode van oversterfte is de sterfte doorgaans lager dan normaal voor die periode.

In 2020 was er oversterfte als gevolg van de uitbraak van COVID-19. In de eerste negen weken van de coronapandemie bedroeg de oversterfte naar schatting bijna 9 duizend mensen, dus ook bijna 2.500 meer dan gemiddeld in de afgelopen vijf jaar. Dit is ongeveer evenveel als tijdens de griepepidemie in 2018, maar het aantal werd nu bereikt in slechts de helft van de tijd. Dat zegt niet per se iets over de ernst van de ziekte want een snellere verspreiding door een hogere besmettelijkheid heeft hetzelfde effect. De curve piekt dan hoger en is sneller voorbij. Wereldwijd zien we steile, kortdurende pieken die hierop duiden.

Het hoogste punt werd in Nederland in de eerste week van april bereikt, toen meer dan 5 duizend mensen kwamen te overlijden, ruim 2 duizend meer dan wat normaal is voor die periode. De coronapandemie begon pas in de tweede week van maart, terwijl de periode van oversterfte tijdens de griepepidemie in 2018 al in de één-na-laatste week van 2017 begon. Door de lagere besmettelijkheid was die curve dus langer en platter: het duurde toen dertien weken voordat het hoogste punt (ruim 4 duizend) werd bereikt.

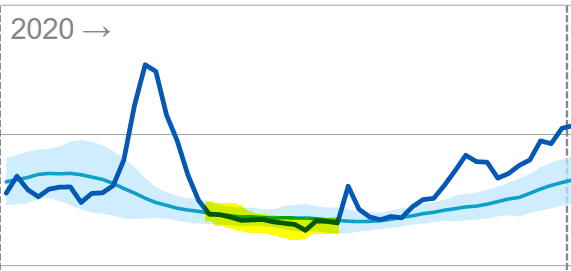

Na de eerste golf van de coronapandemie in 2020 volgde een periode van lagere sterfte (gele arcering). Sinds half mei schommelde de sterfte rond de 2 600 per week. Begin augustus was er voor het eerst sinds 13 weken weer sprake van enige oversterfte, gerelateerd aan de hittegolf. In de tweede week van augustus overleden daardoor 3,2 duizend mensen.

Vanaf half september 2020 liep de sterfte weer op. Sinds eind september was er oversterfte. Dit hield aan tot half januari van 2021.

Substantially higher mortality after March 2021

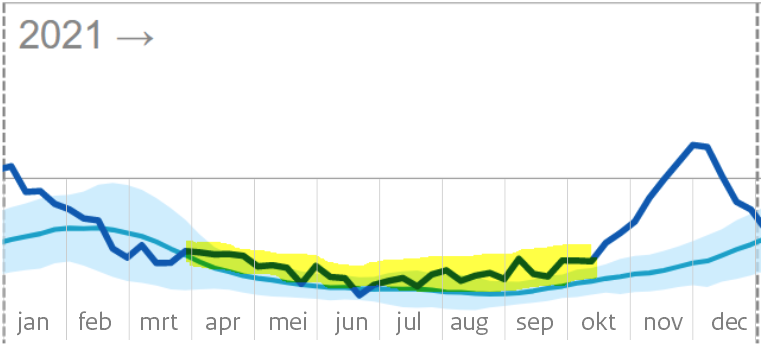

In de eerste weken van 2021 verdween de aanzienlijke oversterfte en dook zelfs, half februari-half maart, even onder de verwachte sterfte. Na een periode van grote sterfte is dit verklaarbaar als invloed van ondersterfte. De lagere sterfte duurde echter slechts 1 maand. Medio maart gingen de sterftecijfers alweer omhoog; de verlaagde sterfte -die opvallend kort aanhield gezien de forse eraan voorafgaande oversterfte- werd daardoor onzichtbaar.

Met ingang van april 2021 bleef de sterfte voor de rest van het jaar structureel boven de verwachte sterfte (gele arcering). Het lichtblauwe gebied geeft de fluctuatiemarge aan waarbinnen de sterfte hoort te schommelen. De pieken en dalen horen elkaar min of meer te compenseren. Zeker in de lente- en zomermaanden is het dan ook zeer ongebruikelijk dat de werkelijke sterfte structureel boven de verwachting schommelt. De enige uitzondering was een kleine dip in medio juni.

From July 2021, mortality will even fluctuate above the fluctuation band

Daarna nam de sterfte steeds verder toe. Vanaf eind juli van 2021 (tijdens de zomer!) oversteeg de sterfte zelfs de bovengrens die bij een regulier sterftepatroon als ‘oversterftegrens’ wordt aangehouden (blauwe arcering). Vanaf half oktober begon de sterfte plotseling nog sneller te stijgen.

Dit zou te wijten kunnen zijn aan de intrede van het herfst-/winterseizoen, ware het niet dat de gerapporteerde covidsterfte ook in deze periode sterk achterblijft bij de waargenomen algemene sterfte. De periode van oversterfte duurt tot het eind van 2021. In de eerste weken van 2022 is de sterfte lager dan oorspronkelijk verwacht. Dit wijst ook op een invloed van ondersterfte van de grote sterfte die kort daarvoor plaatsvond.

Na een periode van aanhoudende hogere sterfte is een periode van lagere sterfte gebruikelijk. Dit is afhankelijk van de leeftijd van de overledenen. Als het ouderen zijn die anders binnen een half jaar tot een jaar zouden zijn overleden, dan is dat snel terug te zien in lagere sterftecijfers van de maanden daarna en ook nog in de griepgolf van het jaar daarna. Zijn het daarentegen bijvoorbeeld vooral dertigers, dan zal er geen duidelijke ondersterfte plaatsvinden op deze termijn. De ondersterfte wijst dus alleen op de overleden ouderen, terwijl oversterfte betrekking heeft op alle leeftijdsgroepen.

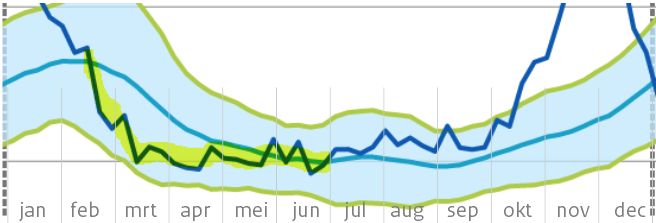

WLZ users

FromWLZGivesstraightop zorg aan verzekerden die blijvend zijn aangewezen op 24 uur per dag zorg in de nabijheid of permanent toezicht vanwege hun aandoening(en) of beperkingen(en).

Dit zijn voor een belangrijk deel ouderen en kwetsbaren. Het is goed te zien dat de ondersterfte daar langer doorloopt, dus niet al eind maart stopt. Dat de totaalcijfers voor de hele bevolking vanaf maart toch weer als “normaal’ kunnen worden gepresenteerd komt dus door hogere sterfte in de andere groepen.

De ondersterfte bij de Wlz-gebruikers maskeert wat er in het voorjaar 2021, te beginnen met april, bij de rest van de samenleving heeft plaatsgevonden.

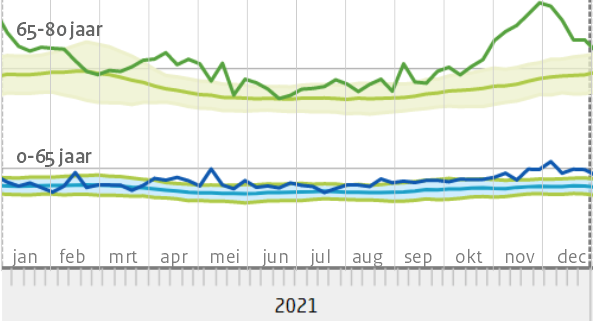

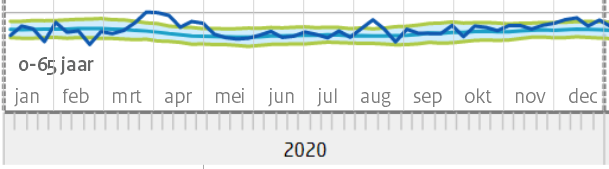

Age groups 0-80

De tachtigplussers-lijn vertoont nagenoeg hetzelfde beeld als die van de Wlz-gebruikers, beide ‘cohorten’ overlappen elkaar. Daarom volgen hieronder alleen de groepen onder 80 jaar. De traditionele rapportage hanteert cohorten 0-65 jaar, 65-80 en 80+. Bij een sterk leeftijdsdiscriminatoire ziekte als Covid is 0-65 te breed gedefinieerd: binnen die groep zijn immers interessante subgroepen te onderscheiden. Dit zou echter een voor de lezer complexer beeld opleveren. Ook ten behoeve van de wetenschappelijke consistentie met eerdere rapportages houdt CBS vast aan de gangbare generalisatie.

In de groep van 65-80 jaar is de sterfte in heel 2021 boven de verwachting geweest met diverse uitschieters tot boven de fluctuatiemarge. Eén uitzondering in week 9: toen waren er zes(!) overlijdens minder dan dan de verwachte 975. In april-mei tekent zich een overduidelijke oversterfte af (boven de fluctuatiemarge). De coronagolf vanaf oktober vertoont grote overeenkomst met die van 2020, ondanks de grotendeels gevaccineerde bevolking.

Ook in de leeftijdsgroep 0-65 jaar is de sterfte sinds maart 2021 structureel verhoogd geweest en niet meer tot de verwachte waarde gedaald, zelfs niet in de zomer. Een verklaring hiervoor zou in de doodsoorzaken te vinden kunnen zijn.

De eerdere bewering “In de weken erna [na half januari 2021, red] was er geen oversterfte” geeft in die zin een misleidende voorstelling van zaken. Er was wel degelijk oversterfte in die weken. In de gemiddelden komt die niet tot uiting vanwege de flinke ondersterfte bij de groep 80+, die eerder zwaar getroffen was.

Zowel in vergelijking met 2020 als in vergelijking met de voorgaande jaren is er een extreem verhoogde sterfte geweest in 2021. Ook na aftrek van covid-sterfte en een incidentele hittegolf blijft een groot deel van die sterfte onverklaard in een jaar waarin er van alles met de bevolking is gebeurd.

Indien COVID alsnog als dominante doodsoorzaak wordt vastgesteld, wijst dat op onvoldoende effectiviteit van de vaccins. De beslissing tot vaccinatiedrang zou dan mogelijk in een ander daglicht komen te staan.

In het geval de vaccins daarentegen wel degelijk significante bescherming boden tegen Delta en we die dus buiten beschouwing kunnen laten, blijft het onbekend welke ziekte de sterfte dan wel heeft veroorzaakt. Om verdere verwarring hierover te voorkomen zullen de doodsoorzaken uitsluitend in geplausibiliseerde rapportagevorm beschikbaar komen, geredigeerd door het rivm en het CBS, beide onder auspiciën van het Ministerie van VWS. Het staatsbelang prevaleert hier boven kamervragen, WOB-verzoeken en gerechtelijke uitspraken.

Naschrift redactie: extreem verhoogde sterfte, geen ‘oversterfte’ volgens het CBS

Wij beoordelen het als essentieel dat de verbanden tussen mogelijke invloeden op de gezondheid enerzijds en de sterftecijfers anderzijds grondig in kaart worden gebracht. Een duiding zoals CBS die geeft helpt daar niet bij.

Het CBS lijkt net als het rivm te willen schermen met de term “oversterfte” als “sterfte die buiten de fluctuatiemarge valt”. Deze definitie is echter alleen te hanteren bij een reguliere fluctuatie rond de nullijn van de verwachte sterfte. Dit is in 2021 evident niet het geval: de sterfte fluctueert een groot deel van het jaar rond de bovengrens. Zolang dit niet expliciet wordt geconstateerd, hoeven we van verklaringen uit de hoek van de overheid niets te verwachten.

De verhoogde sterfte lijkt inmiddels de kop weer op te steken in week 11 van 2022. We gaan weer richting voorjaar en zomer. Er is geen Covid, wel wat griep. Dit zou hoe dan ook niet mogen doorzetten in april.

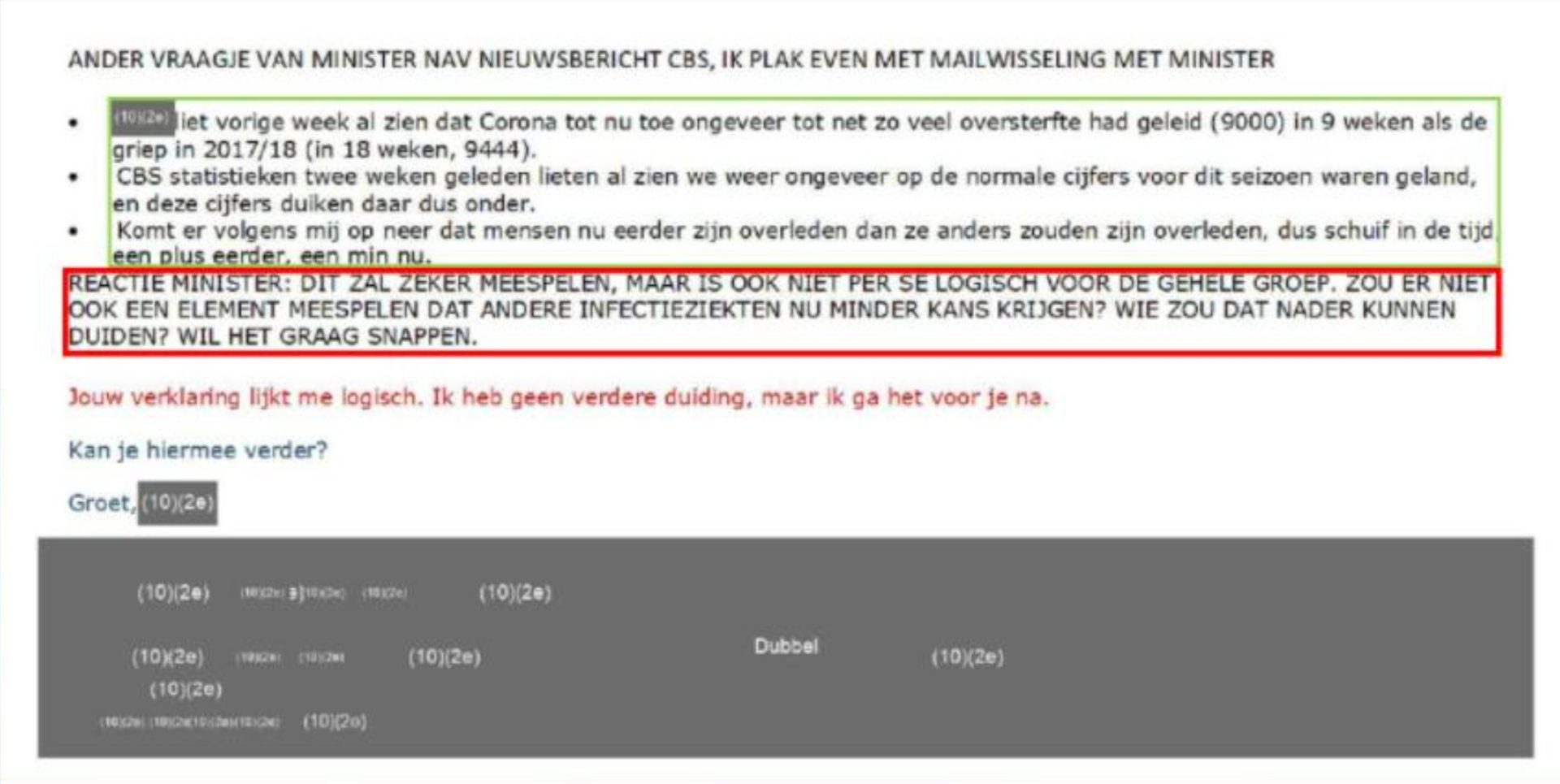

Beste Anton, bij de laatste post gebruik je de oversterftegrafiek van het coronadashbord (VWS) het is misschien interessant hiervoor de oversterftegrafiek te gebruiken van het RIVM. vr gr Karel Balder

Hallo Karel,

Ik heb in dit artikel uitsluitend weergegeven hoe naar mijn idee de toelichting door CBS eruit had kunnen zien. Ik heb alleen gebruik gemaakt van de grafieken die ze zelf ook gebruikten. Behalve in het ‘naschrift van de redactie’. Welke grafiek bedoel je precies, deze? https://www.rivm.nl/monitoring-sterftecijfers-nederland

Voor de duidelijkheid: het zijn natuurlijk niet ‘mijn’ gegevens, het zijn de gegevens van CBS.

Ik heb slechts een -naar mijn idee- meer reële toelichting gegeven bij hun eigen grafieken.

Dat er verschillen zijn tussen RIVM en CBS oversterfte wordt op de RIVM-site uitgelegd:

“De oversterfte schattingen van het CBS en het RIVM kunnen op weekniveau verschillen. Het CBS kijkt naar de gemiddelden over de afgelopen jaren voor de betreffende week, deze zijn inclusief verhoogde sterfte in het griepseizoen. Het RIVM wil juist ook elk jaar oversterfte door de griep in kaart brengen. Om die reden verschillen de schattingen van het CBS en van het RIVM.”

Ik ga me niet in dat debat mengen maar als jij er belangwekkende verschillen in kunt ontdekken, hoor ik graag wat dat dan is!

het zou wel zo duidelijk zijn geweest als vermeld zou zijn waar de cursief gedrukte delen vandaan komen.

Hi Jan, die cursiefjes komen uit dezelfde koker als de rest van de tekst. Ze hebben niet echt een equivalent in het CBS-rapport. Omdat het losstaande nieuwe toevoegingen waren heb ik ze cursief gemaakt.

Ik begrijp de zin “normaal is 6.500 meer dan verwacht” niet (alinea onder de eerste grafiek “oversterfte..”) . Ik zou denken: normaal is wat je verwacht. Waar ben ik abuis?

In 2015-2019 waren er in de griepseizoenen gemiddeld 6.500 meer doden dan verwacht. Elk jaar opnieuw. Dit veroorzaakte geen enkele onrust of maatregel. Dat is dus ‘normaal’. Ik denk dat rivm de ‘verwachte sterfte’ niet aanpast om de griepsterfte gelijke pas te laten houden met de oversterfte. Dat zal wel makkelijker voor ze rekenen. Dus de verwachte sterfte ligt ongeveer 6.500 onder de normale sterfte. https://virusvaria.nl/sterfte-normaal-dus-hoger-dan-het-rivm-verwacht/ Die oversterfte zal flink doorgroeien trouwens: https://virusvaria.nl/oversterfte-binnenkort-naar-ca-10-000-per-jaar/